Russian engineers in exile: creators of ships, bridges, cars

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Russian engineers in exile: creators of ships, bridges, carsRussian engineers in exile: creators of ships, bridges, cars

Svetlana Smetanina

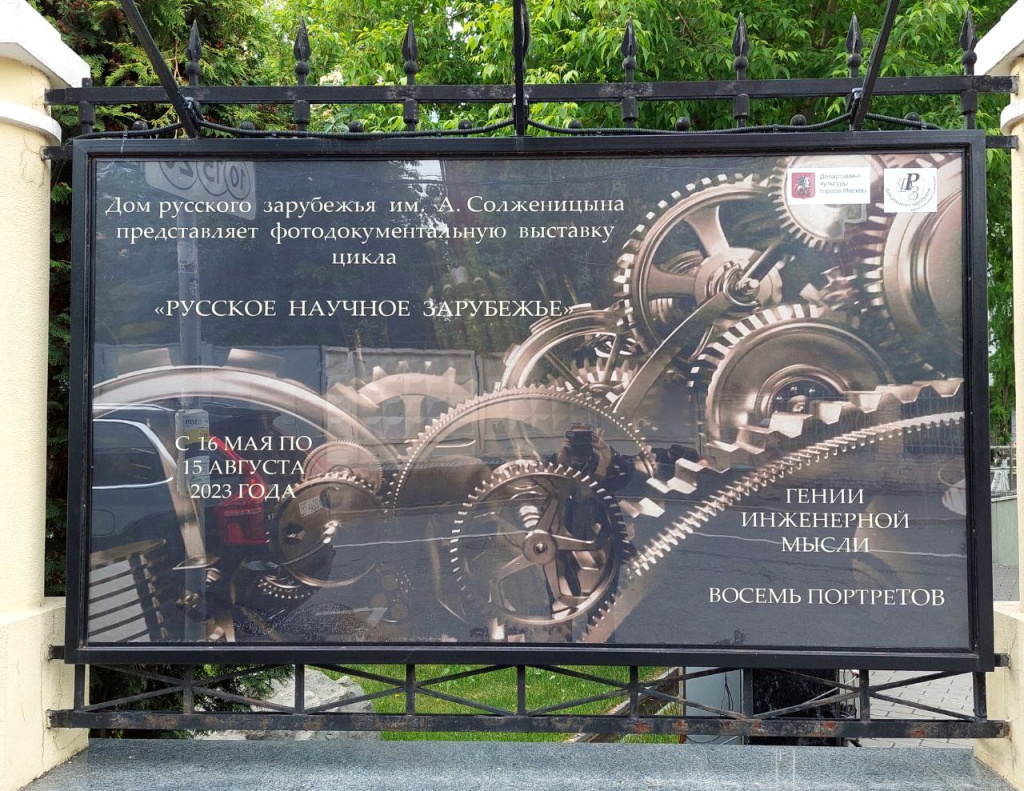

Geniuses of Engineering: Eight Portraits exhibition is now open at the Moscow House of the Russian Abroad. This captivating exhibition sheds light on the remarkable Russian emigrant scientists. While names like Igor Sikorsky, Vladimir Zvorykin, and Alexander Poniatov are widely recognized in their homeland, the general public remains unfamiliar with Oleg Kerensky, Zakhary Arkus-Dantov, Mikhail Zarochentsev, Vladimir Ipatyev, and Vladimir Yurkevich. The exhibition aims to bridge this knowledge gap.

Following the October Revolution of 1917, thousands of of engineering specialists departed Russia. Their individual paths varied upon emigration, yet many found great success far from their homeland. These visionary individuals not only realized their potential but also emerged as exceptional inventors, founders of scientific schools, and pioneers in various fields of production. It is worth noting that Russian engineering thought has made substantial contributions to numerous advancements in the modern scientific and technical landscape of the Western world.

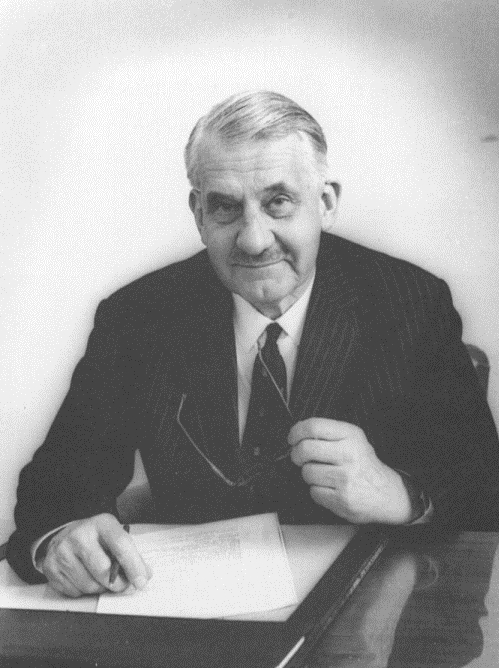

Bridge engineer Oleg Kerensky

Oleg Alexandrovich Kerensky was born in 1905 in St. Petersburg. He was the son of the famous Head of the Russian Provisional Government after the February Revolution. During his education at the prestigious Shidlovskaya Commercial School, he had notable classmates such as the future composer Dmitry Shostakovich and the sons of the artist Kustodiev.

In 1918, the school was closed, and Oleg's family was in a semi-legal status, with his father eventually emigrating abroad. In the summer of the same year, the family experienced a brief period of arrest, but they were released six weeks later. Oleg and his younger brother were fortunate enough to resume their studies. While Oleg's mother initially had no plans of leaving the country, the situation changed when his younger brother fell ill with tuberculosis, and revolutionary Moscow lacked suitable medical facilities. In August 1920, using false passports under the name Peterson, the Kerensky family departed for Estonia. From there, they made a journey through Sweden and eventually reached England, where Oleg reunited with his father. However, by that time, Oleg's parents had divorced, and his father had relocated to America. Consequently, Oleg, his brother, and mother spent the rest of their lives in England.

After attending a private school, Oleg pursued higher education and successfully graduated from university, eventually embarking on a career as an engineer. He joined a British company, playing a major role in the design of the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge, one of the largest steel arch bridges in the world. His engineering expertise extended to the creation of numerous road bridges and other significant structures throughout Britain. Notably, his design served as the foundation for the suspension bridge over the Bosphorus Strait in Istanbul.

In one of his interviews, Oleg Kerensky humbly attributed his success to luck."I made it, I was lucky," he has stated. Widely regarded as one of the finest bridge engineers of his era, Oleg held the position of president at the Institute of High-Rise Building and was a respected member of the London Royal Society. Recognizing his contributions, international conferences known as the "Kerensky Readings" have been held every two years since the mid-1980s in honor of Oleg Kerensky's achievements and legacy.

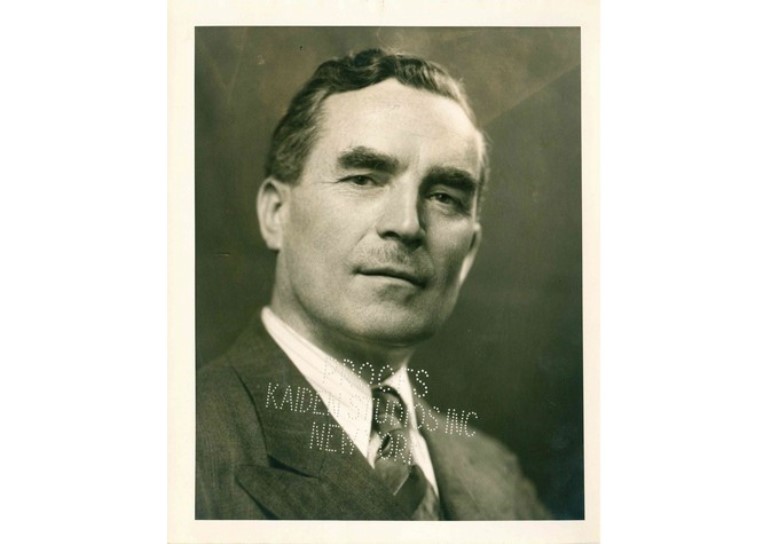

Zachary Arkus-Dantov, the Savior of the Chevrolet Corvette

Zachary Arkus-Dantov, born in 1909 in Belgium to a Jewish family of Russian heritage, had an impressive life journey. His father worked as a mining engineer, while his mother pursued a career as a doctor. After the family's return to Russia, a young Zachary was driven by his passion for technology and mechanics. He was admitted into the engineering department at the Leningrad University.

In 1927, Zachary's family relocated to Berlin. First of all, he acquired a powerful motorcycle, with which he fearlessly raced through the city streets. However, concerned for his safety, his parents advised him to trade the motorcycle for a racing car.

In 1934, Zachary completed his studies at Charlottenburg University of Technology (now known as Technical University of Berlin). Concurrently, he began publishing his engineering works in a German automobile magazine. As the persecution of Jews intensified in Germany, Zachary sought refuge in France, where he and his brother joined the French Air Force. However, following France's rapid defeat, he and his family successfully immigrated to the United States in 1940.

After settling in New York, the two brothers established their own company, executing defense contracts and manufacturing engine parts for Ford. Eventually, their business eventually went bankrupt. Zachary traveled to England, where he secured a position as an engineer, mechanic, and a tester. He prepared cars for races and even became a racer himself.

In 1953, the American automotive company General Motors unveiled Chevrolet Corvette, the first American sports car. Although it was initially met with enthusiasm, later the Corvette faced poor sales due to its underpowered engine. Zachary Arkus-Dantov was hailed as the "savior of Chevrolet." He penned a detailed letter to the company's management, outlining the technical challenges and proposing solutions. Impressed by his expertise, General Motors hired him on May 1, 1953. Zachary went on to develop a new three-speed automatic transmission and an enhanced engine for the Corvette, significantly improving its acceleration and performance. He personally raced and won competitions with the car. Soon the sales have skyrocketed. Under Zachary's guidance the Corvette became the only mass-produced American sports car with over million units sold.

Zachary Arkus-Dantov devoted 22 years to the new vehicles design. He has retired in 1975 as the chief engineer of the Corvette, though he remained a consultant for some period of time. His ashes were laid to rest at the National Corvette Museum, forever commemorating his invaluable contributions to the automotive engineering and the iconic Corvette brand.

Mikhail Zarochentsev, the freezing products expert

Mikhail Zarochentsev. Photo: House of Russian Abroad

Mikhail Trofimovich Zarochentsev was born in 1879 in Stavropol. He had an impressive academic and professional background, obtaining degrees from the Tiflis Pedagogical Institute, the Institute of Railway Engineers in St. Petersburg in 1907, and the Moscow Commercial Institute in 1910. It was during his studies that he developed a keen interest in the science of freezing and preserving food.

Under the guidance of Professor Dmitry Golovnin, Zarochentsev established the Committee on Refrigeration within the Moscow Society of Agriculture. On March 5, 1910, he delivered a significant public presentation highlighting the importance of refrigeration in agriculture, transportation, trade, and industry.

During the First World War, Mikhail Zarochentsev played a pivotal role in supervising the construction of food storehouses, refrigerating plants, and facilities for freezing and packing meat. These efforts were essential for supplying the army and the general population. Under his leadership, approximately 3,000 refrigerated railway cars were constructed. However, following the October Revolution, he found himself in the South of Russia and was eventually evacuated from Novorossiysk to Constantinople in 1920.

In the subsequent years, Zarochentsev continued working with refrigeration systems. He lived and worked in Estonia, Italy, and France. In 1932, he relocated to the United States, where he swiftly rose to the position of vice-president of a frozen food corporation. Throughout his career, Zarochentsev obtained over 200 patents for his refrigeration inventions, which he successfully implemented not only in Europe but also in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and India.

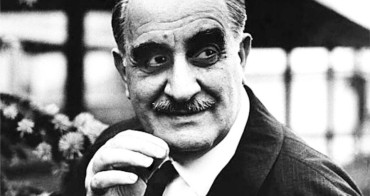

Vladimir Ipatyev, the outstanding chemist

Vladimir Ipatiev. Photo: wiki2.org

Vladimir Nikolayevich Ipatiev was born in 1867 in Moscow into a noble family. His parents planned for him a military career, and assigned him to the 3rd Moscow Military Gymnasium. But 14-year-old Vladimir became seriously interested in chemistry. As he later described it himself, "I was struck by the orderly coherence of the chemical phenomena, it seemed to me that I looked at the world with open eyes for the first time."

Ipatiev joined the Russian Chemical Society, which was chaired by Dmitry Mendeleev. Ipatiev taught chemistry at Mikhailovsky Artillery School and the Academy, defended his dissertation, for which he was awarded the Butlerov Prize.

In 1899 he defended another dissertation in chemistry (there would be three of them in all) and received the title of academy professor. By 1914, Ipatiev was a major general, a corresponding member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, one of the leading experts in petroleum refining and heterogeneous catalysis in organic chemistry. He organizes the chemical industry in the country, heads the production of explosives.

In April 1916, Vladimir Ipatyev headed the Chemical Committee at the Main Artillery Directorate, which included all the leading chemists of the country. The main task of the committee was to establish its own production of explosives for military needs. Under Ipatyev's leadership, new state-owned factories were built and private enterprises were expanded. As a result of the Committee's activities, the production of explosives in the domestic industry increased from 300 thousand to 2.7 million poods per year. It can be stated that Ipatiev practically organized the military chemical industry in Russia from the scratch.

After the October Revolution, Ipatiev at first did not immigrate. Since 1921, Vladimir Ipatiev headed the Main Directorate of Chemical Industry VSNX. In 1927 he became the winner of the Lenin Prize. In 1927, he became the winner of Lenin Prize (Lenin highly respected the scientist and called him "the head of our chemical industry"). At the same time, he organized and headed the Laboratory of High Pressure in Leningrad, which was soon transformed into the Institute. In addition, Ipatiev organized four more educational institutions in the USSR, which trained chemistry specialists.

In 1930, Ipatyev went to the International Energy Congress in Germany, from which he decided not to return to the Soviet Union. Subsequently, he moved to the United States. In 1936 he was expelled from the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and in 1937 he was deprived of Soviet citizenship. The same year he was named "Man of the Year" in the USSR.

Vladimir Ipatyev became a professor at Northwestern University in Chicago. He was considered one of the founders of the petrochemical industry in the United States. In 1936, he discovered catalytic cracking, which significantly increased the yield of gasoline when refining crude oil. Later he invented high-octane gasoline, which brought American airplanes a decisive speed advantage during World War II.

Until his death, Vladimir Ipatyev dreamed of returning home and even appealed to Soviet Ambassador to the United States Andrei Gromyko about it, but never succeeded. In 1953, he passed away. Vladimir Ipatyev was restored posthumously in the list of members of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in 1990.

Vladimir Yurkevich, the shipbuilding engineer

Vladimir Yurkevich. Photo: House of Russian Abroad

Vladimir Ivanovich Yurkevich was born into a noble family in Moscow in 1885, led an illustrious career in engineering. He completed his education at the shipbuilding department of the St. Petersburg Polytechnic Institute and after studied at the Kronstadt Naval Engineering School of the Navy. Yurkevich's expertise led him to work in the Baltic Shipyard design bureau. Yurkevich contributed to the development of designs for battleships, military cruisers, and submarines. During World War I he played a key role as one of the architects behind the project for Russian super dreadnoughts.

Following the Russian revolution, Yurkevich became involved in the White movement. However, in 1920, he was forced to evacuate from Nikolaev to Constantinople aboard an unfinished tanker. In 1922 he relocated to Paris, where he took on positions as a turner and draftsman at the Renault plant. Yurkevich's career trajectory took a significant turn when he secured a job at a prominent French shipbuilding company specializing in large passenger liners. There he developed a revolutionary passenger ocean liner for transatlantic routes. Yurkevich's project displayed superior characteristics during model testing out of the 20 proposed designs. His version became the basis for the construction of the Normandy ship, the largest, fastest, and most comfortable transatlantic vessel of its time, launched in October 1932.

Following this remarkable achievement, Vladimir Yurkevich established his own design bureau. In 1937, he moved from France to the United States, where he served as a technical consultant for the US Maritime Administration. He also held teaching positions at the University of Michigan and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, imparting of his knowledge and expertise to future generations. Yurkevich assumed leadership of the Union of Russian Marine Engineers in Exile, further solidifying his influence in the field. He passed away in 1964, leaving behind a legacy of remarkable engineering accomplishments and contributions to maritime engineering.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...