"I first fell in love in Russia." A Colombian physicist translates Turgenev's novel

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / "I first fell in love in Russia." A Colombian physicist translates Turgenev's novel"I first fell in love in Russia." A Colombian physicist translates Turgenev's novel

Sergey Vinogradov

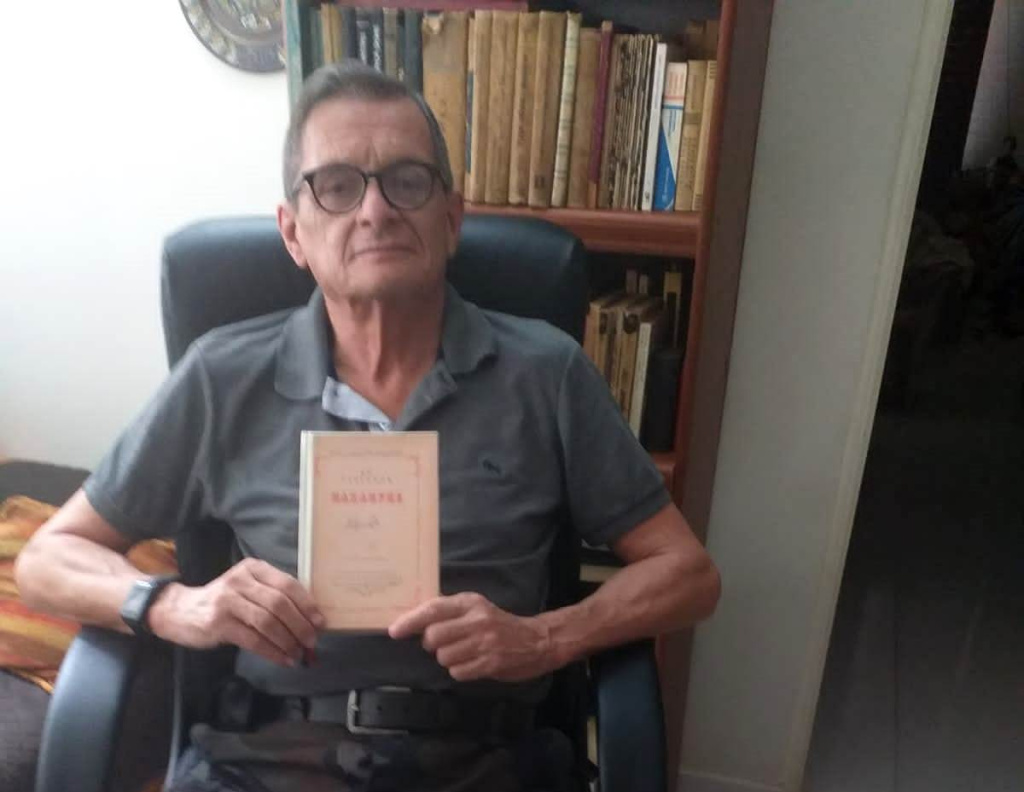

Doctor of Sciences in Physics and Mathematics, the member of the Academy of Sciences of Colombia Gustavo Zambrano Romero was invited by the Columbian Club of Russian Literature Lovers to present his translation of Ivan Turgenev's On the Eve novel. It was Mr Romero's first experience in this field.

Photo: Gustavo Zambrano Romero

Once in Bogota and seeing the Russian embassy, the physicist recalled how more than half a century ago he walked down those steps of the then Soviet diplomatic mission into a new life. He went to study at the Peoples' Friendship University in Moscow.

Gustavo Zambrano Romero told the Russkiy Mir how he was mastering Russian language and culture at the age of 18, how he polished his pronunciation on romantic walks and in student teams, and how he was looking for a job in anti-Soviet Colombia. And finally, he explained why he has decided to engage in the translation of Russian classics, being the Doctor of Sciences in Physics and Mathematics at the age of 60.

Studies in the USSR

- Was your family somehow related to Russia or science?

- Absolutely no. I was born in Santiago de Cali; it was a pretty provincial little town in the 1950s. My family belonged to the middle class, neither poor nor rich. My father worked in a bank for a long time, then he switched to an American company that made cardboard products. My mother, like many women at that time, was a housewife. They haven't graduate from college, only school, which was considered normal back then. By the way, women in Colombia did not have the right to vote until the late 1950s or early 1960s.

Our family was not rich, but my father did all his best to give me a good education. I went to a private school. Not the most expensive, but very good, especially in the fields of math and physics. We studied for 12 years, and from about the 10th grade I started to get interested in physics, philosophy, and psychology. I also became interested in science and the Soviet Union, when I subscribed to the Soviet Union magazine. A big role in my life at this time was played by one of my teachers: He opened another world for us. It was as if I was asleep, and suddenly I woke up, and a veil had fallen.

Photo: Gustavo Romero

- What was the attitude toward the Soviet Union during your youth in Colombia?

- There was a coup in Colombia in 1953. New dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla broke off relations with the Soviet Union, which were restored in 1968. People were influenced by myths around the Soviet Union about various horrors for a long time. For example, that Soviet children were hold by the state to be raised. Illiterate citizens believed various myths. On the other hand, there were many admirers of the Soviet Union among intellectual young people, there were many progressive movements.

- How did you get into the Soviet Peoples' Friendship University (now RUDN)?

- After graduating high school, I was accepted in three universities in 1970. Since my parents couldn't support me in another city, I went to Cali university where I am teaching now. The political situation among students was quite turbulent at the time. The university was closed at once, I have managed to finish only the first semester. So I made up my mind applying to the Friendship House between Colombia and the Soviet Union for a grant. I passed the exam and got the opportunity to study in the USSR. Everything was paid for, even the ticket. In August 1971, I when I was just 18, I left for the Soviet Union. My father had to write a letter of permission to leave because I was a minor. Throughout our studies we received a stipend

- How did your parents react to your departure?

- It was the time of the Cold War, and my parents, let's put it this way, were worried. My father who decided everything in the family, said that my desires and opportunities were broader than what I could get at that time in Colombia. So they let me go.

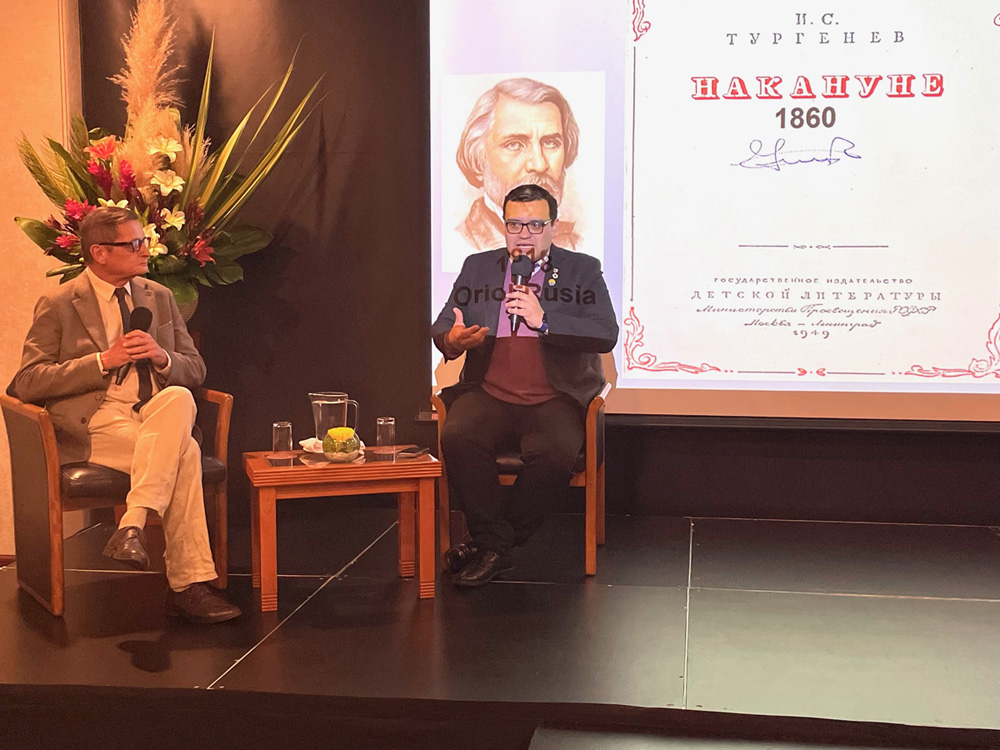

Photo: Presentation of a translation to the Russian Literature Lovers Club

A man "from there"

- Did you have to learn Russian from the scratch?

- Yes, when I arrived in Moscow I knew absolutely nothing except "yes", "no" and "hello." There were Russian language courses at the House of Friendship, but I didn't take them because they were in Bogota. There were excellent RSL teachers at the Peoples' Friendship University. You know, many Colombians go to the United States and learn English on the street. In this case the vocabulary can't be broad, one doesn’t get the essence of the language. In the USSR I had the opportunity to learn Russian from professionals.

The first semester we studied Russian intensively, then we have started math and chemistry in Russian with terminology at the faculty with everybody else. For me it took six years to study, and at the end I got my MA in Physics. After that I have returned to Columbia, and a few years later I went to post-graduate school in the USSR.

- What was the most challenging thing about learning Russian?

- Some people say that the most difficult thing is the Russian alphabet. Not only that, the alphabet can be learned. Real difficulties start with phonetics: about 5 - 7 phonemes are missing in Spanish. I have a mathematical mind, and I knew right away that I had to learn all the complicated things to master the language.

- Did the Soviet diploma help you get a job in Colombia?

- Not right away. The Cold War was still going on, I was looked upon as someone "from there," who had unknown thoughts in his head after returning from the Soviet Union. Naturally, coming back we spread Russian culture and Soviet ideas, because we were grateful that the USSR had given us everything. I started giving lectures by the hour, with no contract. Then I took three courses, worked night and day. It was hard. Then I managed to get a job as a teacher on a permanent basis. At the end, the Soviet education helped, especially after post-graduate school in the USSR. I was writing papers on plasma physics and wanted to continue my development in this field.

Gradually, the attitude toward the USSR in Columbia was changing. As the saying goes, you can't cover the sun with your hands. Many began to understand that this country was the first to send a man into space and made tremendous achievements in nuclear physics and other spheres. In addition, people in Colombia knew and read the Russian classics of the 19th century - Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and so on.

No Turgenev Birds in Colombia

- Why did a physics teacher who specializes in plasma physics decide to translate Turgenev?

- There are, as always, subjective and objective moments here. Coming to the Soviet Union at the age of 18, I really embraced the Russian culture and was able to feel Russian people. I worked in construction, went twice to Siberia and once to Central Asia. And I talked to a lot of people.

The important point is that I fell in love for the first time in Russia. She studied at the philology department, was in the Komsomol and was the daughter of a colonel of the General Staff. I couldn't go to her house, so we walked the streets, and she read me poetry. I adored Yesenin, Blok, Lermontov... Our love lasted for two years. She helped me to speak Russian without mistakes, so it wouldn’t be so obvious that I was a foreigner. I looked like a Georgian to Russians. And it worked. Moving into their third year, I was reading Dostoevsky in Russian. He is my favorite writer, by the way.

Photo: with friends in Russia

- One thing is to love Russian classics and another thing to want to translate it...

- I'll tell you how it turned out. I read a lot on my vacation time. One day I took Turgenev's novel On the Eve. There is an episode when the main characters Insarov and Elena go to Bulgaria through Italy. There's a piece where they ended up in Venice, and that description made a very strong impression on me. It's just one page. And so my wife could read it too, I sat down and translated that page the best I could. My wife liked it, she also loves Russian classics.

I have a fellow Colombian, he is a geologist and lives in Mexico, and he is a professional translator of Russian literature, too. He has translated Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Blok, and others. I sent him my translation, and he commended, "Why don't you translate the whole book?". My first reaction was, "Are you crazy?" I don't have a lot of free time, I have students, graduate students, post-graduates... But something remained in me after our conversation, and I took on the translation.

It took about two years, I worked on Saturdays and Sundays. Plus I wrote comments at the bottom of the pages, explaining some points unknown to the Spanish-speaking reader. Since then, I've started translating.

Of course, I want to publish; I'm talking to publishers. In addition, I plan to start translating Dostoevsky. I don't think I should start with Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov. I was attracted to A Gentle Creature story, which I read when I had studied in USSR.

- What difficulties did you encounter during your translation?

- When I came back to the Soviet Union for my post-graduate studies, I reached an even higher level of proficiency in the Russian language. I could walk into a beer bar, talk to a Russian person for an hour or an hour and a half, and he wouldn't know that I was a foreigner. Well, talking about the translation difficulties... I read without dictionaries, but translation is another matter. When I read, I feel the words, I know what the writer wants to convey. I have to look in a dictionary if I encounter names of birds which don't exist in Colombia, or plants, or horse breeds. My precious Russian-Spanish dictionary helps me a lot.

- How do you maintain your Russian language, living for many years in a foreign speaking environment?

- I do that by communicating with Russian friends, reading Russian literature and Russian newspapers. But the main thing is the luggage of knowledge and experience I brought from the Soviet Union. Russia and the Russian language are always in my head and my heart.

New publications

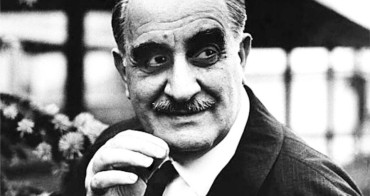

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...