Harbin: Russian Wharf in the Land of China

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Harbin: Russian Wharf in the Land of ChinaHarbin: Russian Wharf in the Land of China

Harbin Saint Sophia Cathedral built in 1907. Photo credit: bigpicture.ru

The year 2023 marks the 125th anniversary of Harbin, a Russian city in the land of China. It was founded on the banks of the Songhua River as a central station of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER). The city was built by Russian architects and inhabited by Russian people. According to one of its residents, the city used to feature a "preserved Russian lifestyle" until the middle of the twentieth century.

City on the Songhua River

The city developed in record-breaking time. There had been only a small Chinese village in the area before it was founded. For half a century, Harbin adhered to the living principles of pre-revolutionary Russia. At the same time, it was an outpost of Russian culture abroad. No wonder Harbin is still known by one of its unofficial Chinese names as Oriental Moscow.

The most accurate date of Harbin's foundation is May 16, 1898. It was the day when the first barrack for the CER builders was laid. Later, a small settlement known as Old Harbin was built around it. Harbin is a Manchu word and means either a ford or a place for drying nets.

The city plan was designed by the famous engineer Adam Szydłowski. The plan was found to be so successful and even today, Harbin, a city with a population of six million people, is developing according to his ideas. It was Mr. Szydłowski who determined the location of the city. He chose the intersection of the railroad and the Songhua River, the main waterway of the region.

CER was under construction based on an agreement with the Chinese government. It was supposed to connect two existing Russian railroad lines, namely, Ussurian and Siberian ones. In this case, the total railway length was reduced by 514 versts. The road was built quickly, and its operation began in July 1903.

Major General Dmitry Khorvat was appointed the chief of the China-Eastern Railroad. The territory adjacent to the CER was prospering during his time. Deserted Manchuria became something like Chinese California. This place was a magnet for business-minded Russians, Chinese, Koreans, Americans, etc. The population of this region grew from 8 million to almost 16 million within only five years of CER's foundation.

Chinese Eastern Railway service saloon carriage (1902 model). Photo credit: George Shuklin / wikipedia.org

However, sometimes things were not that positive. In 1900, the city survived a siege by the Chinese rebels, the Yihetuan Movement. In 1910 - 1911, it faced a plague epidemic. In the 1920s and 1930s, Honghuzi gangs kidnapped people for ransom and robbed trains in the suburbs.

However, all of the above did not affect the rapid development of Harbin thanks to the railroad and its favorable location. Once construction started, it started to expand at a phenomenal pace. As of 1899, the city had 19,000 civilians and military personnel. The 1903 census showed 15,000 Russian nationals, and 28,000 Chinese ones. The total population of the city was about 45,000. By 1917 the number of Harbin residents exceeded 100,000 people. There were over 40,000 Russians among them.

The city had a Commercial School where the best Sinologists taught Russian to students. There was a Society of Russian Orientalists. Their works were published in Harbin magazines. They wrote textbooks on Chinese history and translated Chinese literature into Russian.

Nevertheless, the Russian population of the city lived within the Russian environment without being immersed in Chinese culture (and vice versa was true as well). Both Russians and Chinese preferred to settle apart.

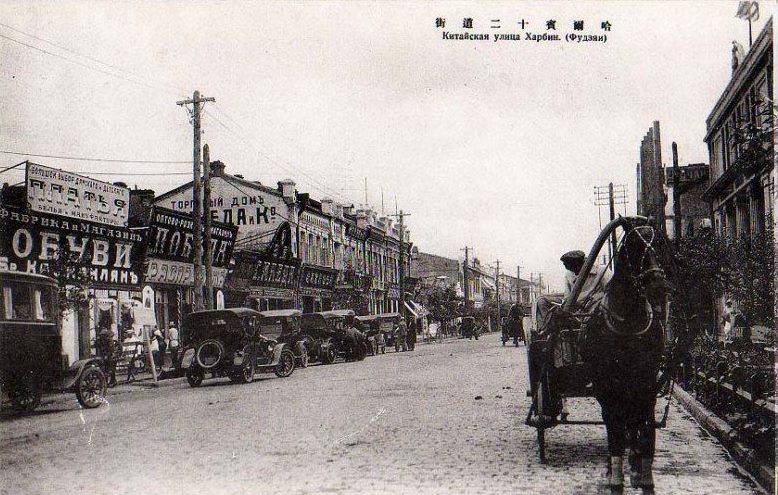

Judging by the standards of the Russian Empire, the city enjoyed a prosperous life (mainly owing to significant government investments in its development and generous salaries of CER employees). In general, Harbin had a Russian face. "One could sense a typical Russian provincial tradition even in how Harbin was developed. First, the coastal part was built. Later this area was referred to as the Wharf. The streets had Russian names, such as Artilleriyskaya, Kozachya, Kitayskaya, Politseynskaya, Aptekarskaya, Kommercheskaya," a contemporary wrote.

China Street in Harbin. Postcard from the early 20th century. Photo credit: bigpicture.ru

The city gradually got European-style buildings with cozy backyards and flower gardens. Orthodox churches were built. Schools, higher educational institutions, and hospitals were opened. Telegraph and telephone networks were set up. Street names and signs were made in Russian. The city was full of trees and plants, including birches and blooming lilacs loved by the Russians.

Harbin had an active social life. Opera and Drama theaters, cinematography, and cheerful café-chantants operated in the city. Residents enjoyed concerts and dancing events, and an orchestra played in the city garden.

"Life was pretty peaceful without any major social disturbances until the early 1940s. It was a little part of old Russia," wrote Sophia Troitskaya in her memoirs about life in Harbin. "Russian residents had educational institutions for them in Harbin, including primary, secondary, higher, special, technical ones. Those who had a lot of money sent their children after finishing high school (gymnasium) to continue their education in Hong Kong, Czechoslovakia, France, and other countries.

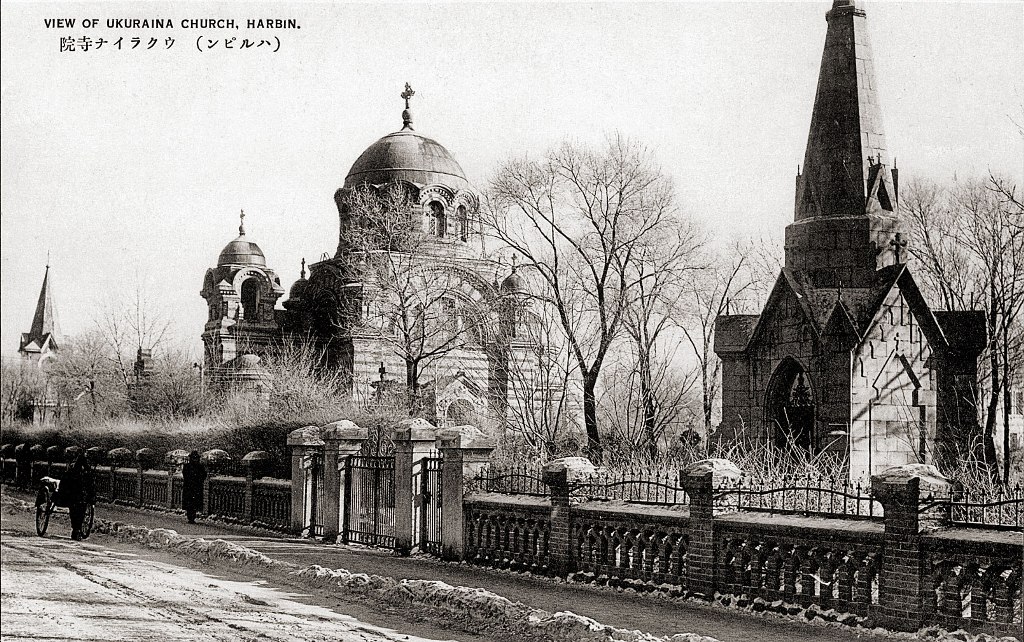

Having settled in China, among the pagans, the Russian people focused primarily on building temples to satisfy their religious needs. Harbin is a relatively small city, yet, 21 Orthodox churches were built there and they all were crowded with worshipers on Sundays and holidays.”

Church of the Intercession, Harbin. Photo credit: ru.wikipedia.org

Harbin used to develop as a multinational and multi-confessional city despite its predominantly Russian spirit. Along with many Orthodox churches, there were two Orthodox monasteries (male and female), as well as two Catholic churches, a Lutheran church, three mosques, two synagogues, three Old Believers' churches, etc. A number of ethnic communities quickly emerged in the city, including Polish, Jewish, Georgian, Armenian, and even Estonian ones…

Center of Russian Emigration

In the 1920s, Harbin became one of the main centers of the Russian emigration. It was here that troops of the Kolchak, Ataman Semenov, and Baron Ungern armies retreated to having been defeated by the Red Army in Siberia and the Far East.

By 1924, the city had about a hundred thousand Russian emigrants. Sixty periodicals in Russian were published here in 1920.

The city's cultural life thrived. Many clubs and associations, including literary, scientific, and artistic ones, were opened. Feodor Chaliapin, Sergei Lemeshev, and Ivan Kozlovsky sang on the stage of the Harbin Opera House. Russian pop star Alexander Vertinsky performed here; and until 1946, Harbin had its own symphony orchestra.

Harbin Winter photo by Viktor Petrov. Russian-American Historical Society Press. Washington, 1987.

Arseniĭ Nesmelov, a member of the White Movement, was one of the most talented Harbin poets of that time. Russian Culture Day was celebrated annually on Alexander Pushkin's birthday, and in 1937 the 100th anniversary of the poet's death was widely commemorated in Harbin.

Scientific life was also developing. The N. Przhevalsky National Organization of Explorers was re-established in the city. It was headed by the famous archaeologist Vladimir Ponosov. The society was engaged in field research in Northern Manchuria, Mongolia, and even Xinjiang. Its members included ethnographers, historians, and archaeologists. Even after the end of World War II, Vladimir Ponosov passed on his archaeological experience to his young Chinese colleagues.

New entrepreneurs came to the city and contributed to the industrial development of Harbin. New industries were formed, such as butter-making, wine-making, cheese-making, etc. New restaurants, stores, and workshops were opened. A cab network was also developing. At the same time, the illegal business of smuggling gems and opium from Soviet Russia prospered.

Despite the city's outward prosperity, many refugees failed to settle there as they faced a life of half-starvation. A lot of them left for the South and joined the Russian colony in Shanghai.

Once transformed into an Oriental center of the Russian emigration, Harbin lost its autonomy. In 1920, a decree of the Chinese government rendered Russian nationals in Harbin equal to foreigners who had no extraterritoriality rights and were subordinated to Chinese jurisdiction. Furthermore, the diplomatic and consular services of Imperial Russia were discontinued in the city. Russian officials were replaced by Chinese ones. The latter informed the CER employees that from that time on they would owe everything to the benevolence of the Chinese administration. Yet, well-trained Russian railroaders and military staff were in demand, as the Chinese simply had no one to replace them.

Russian schools, institutes, and hospitals started to close in Harbin in the mid-1920s. The political split-off was also observed.

The agreement that set the CER legal status was signed between China and the USSR in 1924. It allowed only Soviet and Chinese citizens to be employed in CER. Many Harbin residents took Soviet citizenship to avoid losing their jobs. Others stayed as stateless persons and lost their jobs in CER. Gradually the issue of citizenship and political identity split the Russian population of Harbin into two camps.

Japanese Occupation

In 1932, Harbin, along with other Chinese territories, was occupied by the Japanese and became part of the puppet state of Manchukuo. The Japanese promptly set up a new order. As a consequence, many Russians moved south (to Shanghai) or abroad. In 1935, the Soviet Union sold its share of ownership of the CER to Manchukuo. As a result, many Russian railroad employees with Soviet passports and their families left for their homeland. However, there their fate was tragic.

In 1937, tens of thousands of people were arrested and repressed under NKVD Order No. 0593 with "All Harbin residents are to be arrested..." as the opening line. Many of them were executed or died in the camps.

The Japanese gendarmerie took full control of Harbin. All Russian public and political figures were also under the control of the Japanese administration. Emigrants who had an intransigent attitude toward the Soviet Union served the Japanese. They made up a network of spies and armed detachments to guard the railroad and engage in border provocations against the Soviet Union.

The Russian Fascist Party was strong in Harbin. Many of its right-wing residents were enthusiastic about the German attack on the Soviet Union and even were willing to fight on the German side. During the war, Russian Harbinites were split into "defeatists," who longed for the Soviet Union's defeat, and " defenders," who stood up for the Soviet Union's victory. In all fairness, it has to be added that the latter group was far more numerous.

End of Russian Atlantis

Red Army troops enter liberated Harbin on August 21, 1945. Photo credit: Mil.ru / ru.wikipedia.org

In 1945, the Soviet forces defeated the Kwantung Army and entered Harbin. All residents who had been identified as members of the White Movement and all those who had collaborated with the occupying Japanese forces were sent to the camps.

Following the USSR's withdrawal from Manchuria on April 28, 1946, the administration of the city was taken over by the newly formed People's Democratic Administration under the control of the Chinese Communists.

The Soviet government offered the remaining Russian residents to relocate from Manchuria to "the virgin lands" of Kazakhstan. Some accepted the offer, while others preferred to go abroad.

All of the above changes caused many Russians to leave Northern Manchuria and China between the 1940s and the 1960s.

The rest of the Russians left Harbin during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. At the end of the 1960s, Russian Harbin ceased to exist.

Departing Russians at the Harbin railway station, the 1950s. (Photo from Russian Harbin by O. Goncharenko, Moscow (Veche), 2009)

Harbin residents were scattered around the world, from Brazil to the United States, Canada, and Australia. Having settled in a foreign environment, many of them were nostalgic for Harbin in the early years. Some saw it as their childhood city, while others felt it was the last spot of Old Russia and the Russian lifestyle that they had been used to.

Efrosinya Nikiforova, the last Russian Harbin resident, died 17 years ago at the age of 97. Her death closed the chapter of Russian Harbin in symbolic terms. Many old Russian-era buildings and several churches serve as reminders of the Russian Atlantis.

Russians in Harbin Again

Nevertheless, this story could hardly be complete without mentioning the new wave of Russian history in Harbin. Russian and post-Soviet migrants have resettled in the city since the 1990s, although they have nothing to do with the first wave of emigration or the CER. As of 2015, the Russian diaspora in Harbin included about three thousand people. Currently, there is the Russian Club in Harbin.

The city has six active Orthodox churches. In May 2013, Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Rus' visited Harbin. He served Divine Liturgy in the Intercession Church and visited the Saint. Sophia Cathedral.

Six years ago, in June 2017, the World Congress of Harbin Natives was held in the city. The event was organized by the Harbin City Government to reach out to former Harbin residents and their descendants living all over the world. The forum brought together over 150 participants from China, Russia, Poland, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, Canada, Australia, the USA, and other countries. The largest Russian group came from Omsk. Descendants of Harbin natives also live in Novosibirsk, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Blagoveshchensk, Krasnoyarsk, and Moscow.

New publications

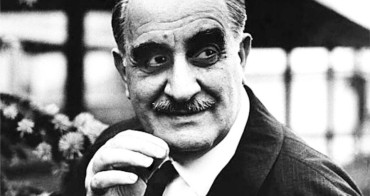

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

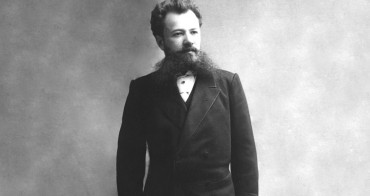

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...