Andrew Nurnberg on Russia’s Prospects in the Literary Market

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Andrew Nurnberg on Russia’s Prospects in the Literary MarketAndrew Nurnberg on Russia’s Prospects in the Literary Market

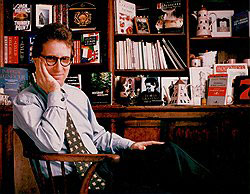

BookExpo 2012 has come to a close in New York. This year Russia was a guest of honor, presenting its Read Russia program aimed at promoting contemporary Russian literature in the English-speaking world. The newspaper Kommersant published an interview about the prospects of this initiative with Andrew Nurnberg, one of the most influential and experienced literary agents representing Russian authors abroad.

– Those who try to promote foreign books in the English-speaking world usually encounter a lack of desire to accept something alien, written in a different language. In this light the prospects of the Read Russia campaign do not seem to be that promising.

– Since there is a great tradition of English literature, which encompasses all genres, then yes, there really is a tendency to reject the other as superfluous, even a certain psychological barrier, if you will. Nonetheless, many foreign-language authors wind up being not only being not superfluous but even very important to the English-speaking world. And I don’t mean just the great Russian classics, as there are more recent examples, such as the success of Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. This book was published for the first time in the West two years ago. Yet then it was only appreciated in intellectual circles. Renowned English write Martin Amis called it the War and Peace of the 20th century, but it did not attract much attention among the public at large. Later, when my agency began to promote this book, we as they say “rediscovered” this writer for the West. Incidentally, a BBC radio play based on the book and performed by renowned actors played a crucial role in this. In the end, Life and Fate was discussed everywhere – in the newspapers and on television. And suddenly the book became a bestseller on Amazon, selling 50,000 copies in three weeks.

– But you cannot say the same about any author living today.

– Not yet. But as I always say, in order to make a country fashionable in the literary world, you only need one author to shoot to the top. This is what happened with Stieg Larsson, who made Scandinavia fashionable. But initially Larsson was not published in either England or America, although he sold well in a number of European countries. Finally a brave publisher was found, and now the sales of Larsson’s books in English exceed sales in any other language, and publishers are printing Scandinavian novels in batches.

– Do you see any writer in Russia with Larsson’s potential?

– Well, at least I haven’t been able to find one. And it is not for lack of trying but rather in some sort of incongruence between what Russians need from literature today and what Europeans need. But I believe that eventual some Russian author will shoot to the top.

– But such a resounding author is really not the same thing as the program of the Ministry of Print which entails grants for translators and publishers working on Russian books. Does this forcing of Russian literature from without seem rather artificial?

– Everybody has grants – all the European countries with the exception of England, because we are rather full of ourselves, have grant programs supporting the translation of national literature into English. However, it seems to me that the most important thing is for the publisher to believe in the book and know how to present it. The best example of such presentation is Penguin’s recent collection of Lyudmila Petrushevskaya’s works. They didn’t try to take an existing book but rather specially selected stories, thought up a great title, commissioned an introduction by a famous book critic and published it right before Halloween, because all the tales are frightening. As a result the book became a bestseller. That is what publishing is all about. It’s not simply translating a text and hoping that everyone appreciates it, as is often the case today. So if the grants stimulate the publishers to approach their work in the right manner, then that would great.

– Your engagement of Russia literature began not very long ago. What do you consider you greatest success?

– I must admit that I haven’t had any true breakthroughs in fiction. To a large degree, I think that during the post-perestroika years many Russian writers strove to breakdown taboos, as this had just become possible. They began to write about “sensitive issues.” As a result, the issues became more important than literature. But in the West these “issues” did not really concern anyone.

With regards to non-fiction, there were breakthroughs, Boris Yeltsin’s books, of course, which sold millions of copies. But that wasn’t on my merits – Yeltsin was already was the most interesting and, I would even say, inspiring politician of his time.

– Would a book by Vladimir Putin, if he were to write one, have such success?

– This would depend on the content of the book. For people in the West Putin is far from being as magnetic a figure as Yeltsin. They would not buy a book based on his name alone. But if he were to write a book about Russia’s place in the world and about how Russia will change, then that kind of book, of course, would be a success.

Anna Narinskaya

Kommersant

| Tweet |

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...