Dahl: Masculine Singular

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Dahl: Masculine SingularDahl: Masculine Singular

In May 1862, 150 years ago, Vladimir Dahl arrived at the session of Russian Philology Society of Moscow University, to present his dictionary, a work of many years, for the consideration of his colleagues.

It is not that nobody had heard about that dictionary, lovingly compiled by Vladimir Dahl, prior to its presentation. A year earlier, Mr Dahl was awarded the Gold Constantine Medal – the highest award of the Imperial Geographic Society – for his lifetime work. And yet only partial records saw the light in 1861 and only the members of Philology Society were given the chance to be the first to see the Explanatory Dictionary of the Live Great Russian Language in full.

They highly appreciated it and the first edition came off the press already in 1863.

Nevertheless, Dahl himself never thought his work to be complete, despite the more than 200,000 entries in the dictionary. Several days before his death the great protector of Russian spoken language, then in his seventies, decided to add four more words after casually eavesdropping on a talk between maidservants.

Incidentally, it is in 1862 that Dahl published another major work – The Sayings of Russian People, containing more than 30,000 sayings, idioms and riddles.

We cannot say the little is known about Vladimir Dahl; rather the contrary is true – his real and alleged actions are still being heatedly debated. To this day attempts are being made to prove that Investigation on the Murder of Christian Children by the Jews published in 1844 and reedited in 1913 as Notes on Ritual Murders were authored by Dahl, even in the lack of any convincing evidence.

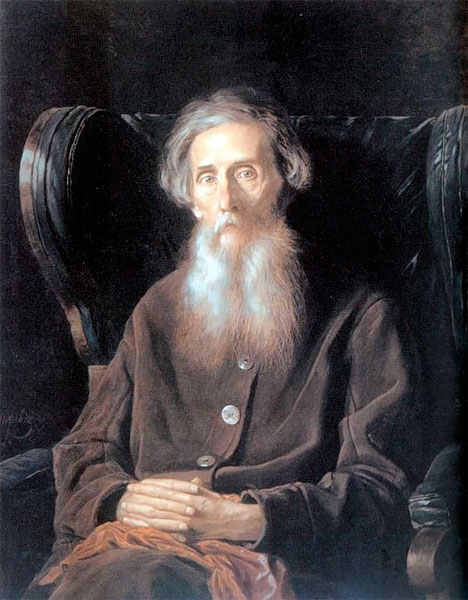

Nevertheless, in spite of abundant knowledge about the compiler of the great dictionary, in the minds of many Mr Dahl is associated with a long-haired and long-bearded monastically looking elder from Perov’s portrait. It is this kind of wise man who was supposed to gather words during his lifetime, searching for their interpretation in the quietude of academic chambers.

Indeed his 70-year odd life was saturated with many events – enough for several lives.

Judge for yourself: Vladimir Dahl was born in 1801 in the town of Lugansky Zavod of Yekaterinoslav Governorate – old Cossack lands – into a well-educated family. His father Ivan, a doctor of medicine, spoke eight languages. His mother Maria spoke five languages and was engaged in writing and translations.

Dahl spent his early years in the southern port of Nikolaev and then studied at the Naval Cadet Corps in Saint Petersburg. From 1819 to 1826 the future creator of the dictionary served as a naval officer – first on the Black Sea and later in Kronstadt on the Baltic Sea. Among his workfellows was admiral Nakhimov. Vladimir also had a go at literature.

In 1826 he resigned and entered the medical department of Dorpat University where he studied with Mr Pirogov. He defended a thesis and diploma and then the Russian-Turkish war broke out in 1828-1829, followed by the Polish events of 1830-1831. Dahl became a famous medical surgeon. In 1832 his successful, but short career of ophthalmologist and surgeon in Saint Petersburg was interrupted. A conflict with his bosses forced Dahl to leave the capital city.

During the following seven years he served as an official of special commissions at Orenburg Governor Perovsky.

In autumn 1833 he received Pushkin who came to Orenburg to gather materials for his book about Yemelyan Pugachev. They became such close friends that Vladimir Dahl was among the few close people at the bedside of dying Pushkin in the tragic days of winter 1837.

In 1839 Dahl participated in the Khivinsky campaign of the Russian Army.

From 1841 Dahl served at the Ministry of the Imperial Court in the capital city and later was employed as personal secretary by Perovsky again, who was then Minister of the Interior. But in 1849 Vladimir departed to Nizhny Novgorod where he works several years as chairman of the treasury chamber.

Only in 1858 did Dahl finally retire and settle down in Moscow.

The remaining years were devoted to the labor of his life – the Explanatory Dictionary – which Vladimir seriously pondered as an 18-year-old naval cadet.

The literary heritage left by the member of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, Lomonosov Awards laureate Vladimir Dahl includes eight volumes of fiction and four dictionary volumes.

I wonder whether the hunter for phrases, sayings and word combinations would be happy nowadays about the chance to fill up his vocabulary with neologisms flooding contemporary Russian. He might be delighted to add another volume to his dictionary as a linguist, but as a reputed Russian man of letters and an academic he would not likely be delighted.

Mikhail Bykov

New publications

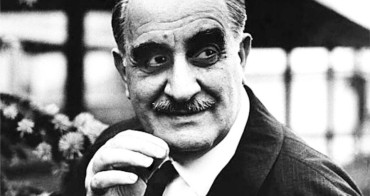

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

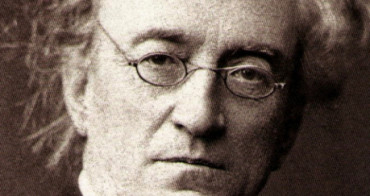

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...