On Prominent Figures and Thick Journals

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / On Prominent Figures and Thick JournalsOn Prominent Figures and Thick Journals

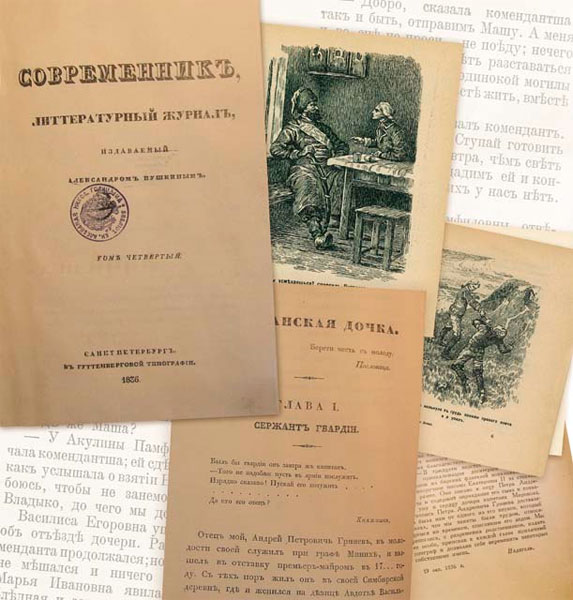

The first issue of the Sovremennik (“The Contemporary”) journal, published and edited by Alexander Pushkin, saw the light in St. Petersburg on April 23, 1836, 176 years ago.

In hindsight, this journal seems to have been guaranteed literary success. Yet one of Pushkin’s contemporaries held to the opposite opinion, writing: “The name of Pushkin as the publisher was sufficient for us to predict that the magazine would have no dignity or the slightest chance for success…”

The name of that contemporary of Pushkin is Belinsky. Interestingly enough, “Frantic Vissarion” spelled doom for the last project of the genius not in the lack of commercial prospects. Number one critic believed that Sovremennik would hardly be able to have any moral influence on the reader.

I should admit that back in my school years I developed a strong prejudice against Belinsky. This figure emaciated with consumptive fits of a lunatic asylum. Vissarion himself spilled the beans that he was more trustful of a priori assessments, i.e. those made before familiarization with an assessed object. This hastiness multiplied by hyper activity and peremptory judgments begat a staunch adolescent mistrust in the critic.

Probably not in vain – after the release of the first two issues Belinsky was firmly convinced: Pushkin was a lame editor, the magazine is not a spiritual beacon, the print-run is shamefully small, and only in Moscow it was possible to sell more than 1,000 copies.

For all that, the critic fully agreed with what was asserted in Sovremennik: “the editor must always be a prominent figure.” In other words, he was self-contradicting, as always.

But what was really happening to the periodical, which was the first in Russia, to fit a rather blurry but now universally understandable pigeonhole of “sociopolitical, literary and art magazines?” We’d rather omit the fact the preeminence in that genre again belonged to Alexander Pushkin.

Four issues were published under Pushkin’s supervision. Apart from the masterpieces of the genius himself, the magazine published the works of Gogol, Zhukovsky, Vladimir Odoevsky, Vyazemsky, Denis Davydov, Fyodor Tyutchev, Baratynsky, Turgenev, the memoirs of cavalry girl Nadezhda Durova…

Not bad for the magazine, unable to wield any moral influence, was it not? Things were much worse with commercial success, though, contrary to the forecasts of the same Belinsky. The first two issues had the print-run of 2,400 copies each, but there were not more than 600 subscribers. The last volume published while Pushkin was still alive had the print-run of 900 copies…

The red ink of the franchise could have various explanations – a loose publication schedule, insufficient frequency (four issues a year), the lack of pungent political polemic, the anti-PR of professional publishers (the likes of Bulgarin and Grech). Pushkin probably suggested the most convincing argument of all: the Russian society just was not accustomed to this type of magazines. In other words, people were not ready.

Be that as it may, the poet’s successor Pletnev held on till 1846, when only 233 subscribers were left. The matter did not come down to the readiness of the broad public in this case, but to the lack of the publisher’s authority and a clear editorial policy.

Sovremennik was twice revived. In 1847 it was bought out by Nekrasov and Panaev. Prior to them it was kept afloat by such personalities as Belinsky (!), Chernyshevsky, Dorbrolyubov, Saltykov-Shchedrin. Published on its pages were the works of Ivan Turgenev, Leo Tolstoy, Gleb Uspensky, Goncharov and Herzen…

In 1861 the print-runs reached the 7,000-copy mark, but five years later the authorities closed down the magazine for political reasons.

In 1911–1915, Sovremennik came out in St. Petersburg, but it failed to rise to the former highs. 20th century Russia (USSR) experienced the century of “thick” journals – the heirs of Pushkin’s pioneer work. Novy Mir, October, Znamya, Yunost, Neva, Aurora, Nash sovremennik, Inostrannaya literatura, Druzhba narodov, Moskva, Lireturnoe obozrenie – what a collection, what wealth! Millions of Soviet people familiarized themselves with the best specimen of literature and journalism, both domestic and foreign, thanks to those magazines, with good and needed books being in short supply, as Vladimir Vysotsky put it.

The print-runs of thick journals in Soviet times were numbered by hundreds of thousand. Many home libraries still feature selections of these editions. There were enough of bookworms who set apart the best works out of the issues and had them bound, thus engaging in some sort of “underground” printing.

Now the extant magazines may boast the print-run of only two or three thousand copies. They are remembered time after a while, discussions spark up in narrow cultural circles on the “to be or not to be” subject, but that’s about all. It’s clear that “editors are not always prominent figures” and publishers are not privileged with as wide the choice as in Pushkin’s or Nekrasov’s times. But they should try to keep their eyes open …

In recent weeks the national leaders increasingly often address the topic of moral guidance, but slogans, tenets and commonplaces are not the best way to reach worthy results. They were haggling a lot about the Public Television in Russia. No longer had a specific decision been taken, though, than the cynical TV get-together stirred a peg and began bubbling up in anticipation of changes.

Literary and art magazines are not an obsolete model used by the writer for meeting with the reader. This is the very moral and professional censorship which sifts through the literature born under our eyes. This is an excellent instrument allowing the clearing of the bookshelves and hence the brains of the reading audience from obvious commercial literary rubbish swamping human minds.

It’s a pity the emperor who appreciated Pushkin’s talent failed to understand it almost two centuries ago. Hopefully the powers that be will finally realize this plain truth?

Mikhail Bykov

New publications

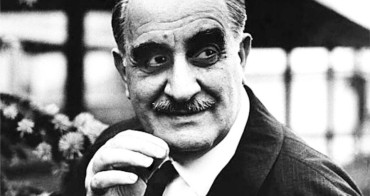

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

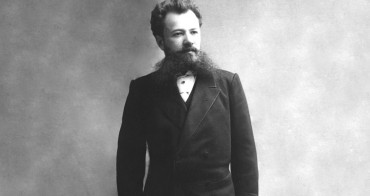

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

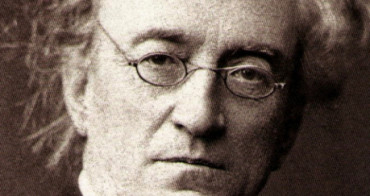

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...