The Era of the Workaholic

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / The Era of the WorkaholicThe Era of the Workaholic

It’s hard to believe but according to the Russian monitoring of economic standing and human health conducted together with the Higher School of Economics, the people of Russia are more loaded with work than the Japanese nowadays. However, the labor productivity remains at previous levels in spite of growing employment, and protest moods are on the rise.

Given such an environment, it has been rumored that on April 28, International Labor Protection Day, or on May 1, the tandem of Dmitry Medvedev and Vladimir Putin may lead the Give Us Justice! march in Moscow. Even if the rumor proves to be a gossip the society has begun rethinking the meaning of May 1, as the festival of an uncompromising stand for labor rights. For even the Russia of the early 20th century and the USSR look as a flowerbed of democracy compared to the beginning of the 21st century. The eight-hour workday, two days off per week, and a guaranteed leave – everything is left in the past. According to the Russian monitoring of economic standing and human health, the average monthly work time duration increased from 153 to 171 hours from 1992 to 2000 and to 185-193 hours by 2011. Thus Russia exceeded the record of Japan where the monthly work time duration comes to 192 hours.

Almost half of able-bodied Russians in their prime years (men aged 18–55 and women aged 18–50) have an average workweek of 43-45 hours. A business day lasting more than 8-10 hours is a norm for the majority. Although the Labor Code strictly prescribes a 40-hour workweek, a significant part of people work from 12 to 14 hours a day. For all that, the paid leave has decreased from 24-28 days to 20 and even 12 days in a number of private companies, which often add the paid leave to festive days or pay no leave allowance at all on various pretexts. As reported by VCIOM sociologists, workaholics do not get any lawful compensation for their overwork either. True, many are content with a different bonus in the form of growing wages and a career growth.

One of the paradoxes is that labor productivity does not increase with the workday extension. HSE sociologists affirm that productivity of labor in Russia remains at the level of the USSR in the 1980’s, slightly surpassing it. “We have a new pre-crisis situation,” laments Vladimir Gimpelson, Director of Labor Research Center at HSE. “On the one hand, we work a lot, more than 45 hours a week, but the productivity grows very little if at all. It cannot be ruled out that we’ve reached the employment ceiling and the employer needs to look for other ways of personnel motivation for labor productivity to grow.”

Not only in Russia, but also in traditionally hard-working Japan and Britain productivity of labor does not grow in parallel with growing employment levels (Japan) and even slightly falls (UK). Yet for now nobody has objected to unpaid overwork either in Russia or in other countries. Companies prefer to motivate their personnel with the help of bonuses instead of proceeding from higher rates which the government binds employers to pay those who work more than 40 hours a week. The law binds the employer to compensate extra loads with extra days off. However the strikes of Ford workers, the miners of Kuzbass and the Urals, the taxi drivers of Kuban, the ambulance doctors, and the railway personnel in Moscow, Yekaterinburg and Novosibirsk demonstrate that even a relatively high or stable salary stops being the only benchmark of effective labor-management relations.

The attitude toward work changed after the crisis of 2008-2009. Thus the share of respondents who now want to have stable even if small earnings and confidence in tomorrow (the post-Soviet model of labor motivation) has dropped from 54% in 1994 to 44% in 2011. The share of those ready to run the risk in order to work much and earn decent money has grown from 28% in 1994 to 34% in 2011. The number of those who are ready to start their own business has notably increased too – from 6% in 1994 to 10% in 2011 (the world’s average figure is 11%). And what is also important, these representatives of nascent small business create jobs for approximately the same number of other people. And finally the percentage of “post-materialistic” labor motivation – those who agree with small earnings for the sake of much spare time – does not exceed 3-4%. Therefore economists assume that in the future the bearers of the post-Soviet labor motivation model will make a real difference. On the assumption of a given and demographic reality – shrinking labor resources and ageing population – economists believe the most acceptable model of labor-management relations in the future is the revival of trade unions, indispensable in the post-Soviet labor motivation model, and market regulation with elements of trade-union movement for “white collars.”

Therefore both the street and authorities have realized that unlimited power of the employer, unrestrained with the obsolete labor regulation, is coming to an end.

The employer has so much enthralled the laborers again that our indignity stalls the growth of labor productivity, contributes to staff turnover, and triggers social unrest. For all that, trade unions in Russia are extremely feeble.

Even in FITUR (Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia), the cradle of unions, the level of trade union movement is such that many of its leaders see the union calling not in standing for workers’ rights, but in offering material help to them and in distribution of hotel vouchers, treatment and travel privileges, etc. Alas, the inability of union bosses to oppose the uncontrolled workweek extension is symbolic. Another reason is that unions are absent as such almost everywhere, particularly among the “white collars.” And wherever they emerge, they contract the inevitable growth diseases – opposition against the law and discord among the union leaders. On the other hand, everybody understands that an era of active labor protection is coming, along with the birth of independent unions, capable of teaching people how to assert their rights assiduously.

Vladimir Emelianenko

New publications

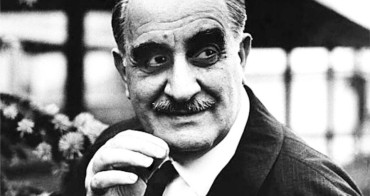

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

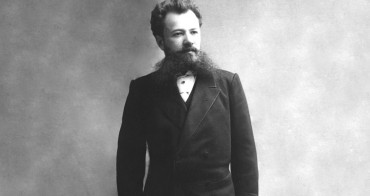

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

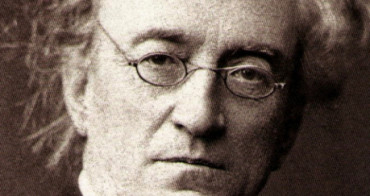

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...