Turgenev’s fellow countrymen

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Turgenev’s fellow countrymenTurgenev’s fellow countrymen

Sergey Vinogradov

The 200th birthday anniversary of Ivan Turgenev will be widely celebrated in November not only in Moscow, Paris and Baden-Baden. Lebedyan, Shchigry and Topki, as well as other towns and villages of the Oryol and Kursk Regions, famed by the writer in his “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album”, have been also preparing for the celebration. Lots of things have changed in these parts, which Turgenev scholars and huntsmen from the Oryol Region call “Turgenevian woodland”, but hunting is still excellent.

Talks in Oryol dialect

In summer and autumn of 1846 young Ivan Turgenev put his pen aside and enthusiastically went hunting in his home grounds. In three to four months he bagged a number of ducks and black games, as well as stories for “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album”, the book which in no time propelled him into the ranks of the top Russian writers of those days. Saltykov-Shchedrin believed that Turgenev had created a new genre of folk prose. However there were those who did not admire his short stories; critical reviews were also heard. Vissarion Belinskiy, then famous literary critic, wrote that Turgenev “goes too far in using Oryol dialect”. The writer was not able to bring a real peasant from the Oryol Governorate to the critic’s door to prove that his description of characters’ speech had been truthful. And records of local rural talks, which can be heard in the folk museum “Turgenevskoe polesie” (Turgenevian woodland) in the village of Il’inskoye, testifiy that Oryol dialect, captured by the writer, was still spoken a half a century ago.

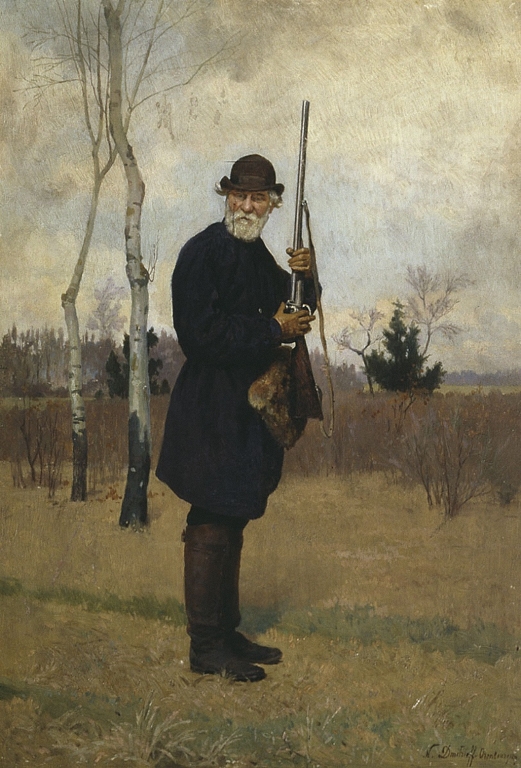

Nikolai Dmitriev-Orenburgsky. Portrait of Ivan Turgenev hunting, 1879

Well if Turgenev did “go too far” in something, it was about Oryol topography. “Has anyone ever moved from Bolkhovskiy parish to Zhizdrinskiy one…” begins “Khor and Kalinych”, the first story in “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album”. Why was it so vital for the writer to mention all small villages and creeks he had encountered along his path? Time and time again admirers of Turgenev’s works have followed the hunter’s traces with “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album” in hand, and in every occasion they are able to verify correctness of nearly all mentioned local names. And if the story states that the distance from one village to the other one is five versts*, it is absolutely accurate - you can check with a car’s trip counter.

But why was he so precise? Maybe he decided to be scrupulously accurate while reconstructing the whole great Russia on a patch of the Oryol Governorate. Or maybe he paid a tribute to inhabitants of certain villages who assisted him with accommodation, advice or a bowl of shchi** when he was writing “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album”.

Versta is a Russian unit of distance equal to 1.067 kilometers (0.6629 mile)

** a Russian soup with cabbage as the primary ingredient

Suchok comes back to Lgov

Lgov is a large steppe village with rather ancient stone church and two mills on the swampy river of Rosota.” This is how Turgenev begins his “Lgov”, one of the most well known short stories in the Sketches. Today Lgov is still a large village – there are more than one hundred households; and the church is still there. For a long period of time it used to be in ruins, but a few years ago the church was restored.

The only thing the classical author made little confusion was about a river. The Vytebet is the river that flows through Lgov, but he concocted the Rosota. Natalia Bolgova, who lives here, believes that the Vytebet was not mentioned in “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album” due to cacophony of its name.

Natalia Bolgova is a Moscowite. For many years she used to visit Turgenevian places to relax her mind and soul; then she joined a local folk music group and plunged into study of dialects. And when she found out someone was selling a good yet inexpensive house in Lgov, she bought it and moved for good. Now Natalia intends to establish the One-story-museum in the village and has already accomplished quite a lot: she bought a plant-filled plot near the church and convinced local authorities to assist in clearing in. She plans to divide the prospective museum into sectors: one will be centered around Russian hunting and Turgenev’s hunting practices, another one will be dedicated to the old man nicknamed Suchock, the lead character of “Lgov” (he is a local in Lgov), and one more sector will focus on local peasant life in Turgenev’s time. “You know, it’s a shame that buses with tourists pass by Lgov, but no one come here, because there is nothing to see, yet,” Natalia Bolgova complains in interview to the Russkiy Mir.

Details and particularities of peasant life have been also recreated in the folk museum of Il'inskoye, a village situated not far from Lgov. Its manager, Lubov Neludimova, founded the museum 26 years ago. “I was the director of a community center; people used to bring me various interesting things from trunks and attics,” she says. “So we decided to open a museum. My husband and I renovated an ancient building.”

You can see there anything and everything: tools, dishes, clothes and many more items. There are some very old things. For example, a frock coat for men – no one can say how old it is exactly, but one of drawings pictures Turgenev wearing exactly the same one. Visitors from all over the world come to the museum “Turgenevskoe polesie” (Turgenevian woodland) on the recommendations given by Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, the memorial house museum. Having experienced interest from locals and tourists, the museum in Il'inskoye has enhanced works to regain spirit of Turgenevian times. Today they know what peasants wore then, what dishes they cooked to welcome the drenched and cold writer, and what they sang for him – in this regard they even organized a folk ensemble in Il'inskoye, found old songs, and the dialect was patterned after records.

Vasiliy Peskov, a well-known journalist, walked down Turgenevian paths in the 2000s. He took his fowling piece along to make sure his impressions would be complete. He describes how he bagged ducks just outside of Lgov and was looking for a small tavern in the village of Kopotovka, which was mentioned in the story of “Singers”. And then how he took a break and relaxed at Bezhin Lug (Bezhin Meadow).

In Turgenev’s garden

Topki, a village in the Oryol Region, was not mentioned in “Sketches from a Hunter’s Album”, but thanks to Afanasy Fet , a Russian poet, it has been associated with “Home of the Gentry”, a novel by Turgenev. One of estates owned by his mother, Varvara Petrovna, was situated in Topki; and he used to bring Fet there for hunting. Later, when “Home of the Gentry” was published, the poet wrote that Vasilievskoe, the Lavretskye’s estate, was depicted by Turgenev based on Topki.

The estate did not survive; you can find only understructures of the manor-house and the guest outhouse, but Turgenevian garden is still there, in Topki. Though nobody takes care of it, fruit trees still bear fruit, and orderly layout can still be noticed. Elena Pavlovna, a teacher of Russian language and literature of local school, brings here her pupils for studying. She is also in charge of school museum, where Turgenev is given a special place.

Topki was the remote estate of Varvara Petrovna; she used to send here insubmissive or delinquent peasants,” the teacher shares. “Part of our exposition is dedicated to the family of Ivan Ivanovich Zamyatin, who was sent here by the lady of the manor. His son, Ardalion Ivanovich Zamyatin, was the first teacher in our school and he left memoirs. For example, he writes about meeting Turgenev in Topki when he was a child. You can still find graves of Ardalion Zamyatin and his daughters, also teachers, in our village graveyard.”

Preparations for birthday anniversary of Ivan Turgenev have been conducted in Topki school for several weeks now: songs have been practiced, fragments for short performances have been put into rehearsal. “Whole school will participate in celebration,” Elena Pavlovna says. “We have only ten pupils, and every one of them will be engaged.” And all inhabitants of small Topki will come as well. Except probably those who will go hunting.

New publications

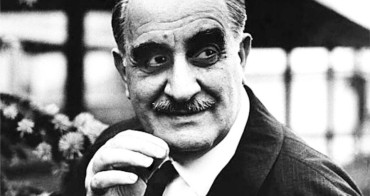

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

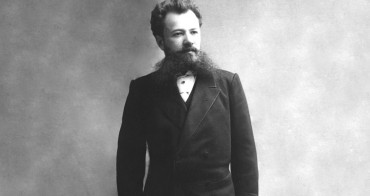

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

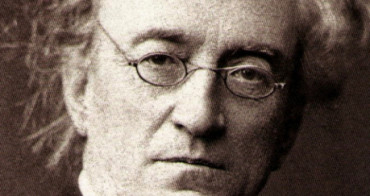

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...