The Beauty of a Russian Christmas

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / The Beauty of a Russian ChristmasThe Beauty of a Russian Christmas

Marina Bogdanova

Winter in Russia is a time of joyful holidays. Christmas and Christmastide—up until the Epiphany—are the brightest and happiest days of winter. How did they celebrate these holidays beloved by the people in Old Rus?

Thanks to the decrees of Peter the Great, Russian cities would turn into forests at Christmas, such was the abundance of fir trees brought in for sale. Vendors of hot saloop bustled amidst the snow-covered fir trees; stores were decorated with lanterns, tinsel, tree ornaments, and Christmas cards; carts with frozen birds and pork drove out to the markets, as the Christmas fast was ending; and the streets were decorated with holiday illumination. Meanwhile, there was no bustle in the village. The village met Christmas in its own way, paying no mind to the fashionable hubbub of the city, instead following the traditions of old.

Nativity Play

Christmas and the surrounding holidays are special days in the folk calendar. Fortunetelling, traditional entertainments, ceremonial foods, and the great number of superstitions associated with these holy days—all this has gone on since the distant past and continued to exist all the way to early 20th century. But if Shrovetide could continue to be celebrated in the USSR as an element of folk celebration, it was impossible to remove the Christian component from the Christmas week celebrations. Christmas traditions were strictly forbidden as religious propaganda. The new government also banned the New Year’s fir tree, but it was “pardoned” several years later. But bringing back Christmas was unthinkable.

The Christmastide celebrations remained as strange days when “young ladies tried to tell the future,” but the deeper meaning of this holy time, its movement and inner philosophy were banned—and alas, in many respects they were lost. The tradition of folk blessings and carols was cut short. And you don’t see Nativity puppet shows anymore—except among folklorists and reconstructions that have carefully preserved memories of the past.

And yet, Nativity puppet shows existed in Russia approximately from the 16th through the 17th century. Researchers believe that they came to us via students at the Kiev seminary, the tradition of puppet mystery plays gradually became an indispensible part of folk devotion, from the Mogilev Governate all the way to Siberia. It was a surprising amalgam of seemingly incompatible traditions: archaic fertility rituals and Christian didactic literature, folk songs and “learned” scholastic poetry, the shameless merriments of the carnival and the sacred story experienced in its fullness by all participants in the performance—all this came together in the folk theater, the Nativity play.

The very word for Nativity play, “vertep,” means cave in Old Church Slavonic. This was where the Holy family hid from Herod’s soldiers. As often happens with language, the word “vertep” gradually changed its meaning, later coming to signify a thieves’ hideout, a place where nothing good can happen to you.

A number of churches make a modest dwelling, a vertep, out of fir branches and place below them the icon of Christmas or the Holy Virgin with her Child, and then anyone coming to worship at the church seems to be standing at the entrance to this very dwelling, along with the shepherds and wise men.

But the real vertep was a quite complex construction. A large wooden box with closeable doors and opening, entrances and exits, was divided into two levels. The openings had an important purpose: they allowed the puppets to move around—they could enter and exit through the doors.

The vertep was often made in the shape of a church or a beautiful cottage. The upper section represented the manger where Christ was born. A little crib was placed there, or sometimes a bassinet was hung in the depths. The Star of Bethlehem has hung up high, with a candle placed in it so that it actually shone.

The main action took place down on the first level: there was the lowly, sinful world, where King Herod’s throne stood and all of his wicket deeds transpired. At the very bottom was, of course, Hell, and terrible devils leapt from there, carrying their victims off with them.

The doll was carved of wood, painted, and dressed in bright costumes. So that everything would be visible, they were put on special handles that went into the openings like grooves, allowing these characters to slide along the stage.

Overall, the vertep was supposed to look rich and colorful—it was decorated with foil, pictures, beads, ornaments, and painted angels. They tried to paste a blue or white cloth on the upper level, to make it look like the sky.

The collection of dolls was more or less determined: the first part, the mystery, required the Holy family, an Angel, Three Wise Men, Shepherds, Old Rachel, Death, King Herod, his Soldiers, and the Devil. These were the requisite characters of the mystery. Sometimes Herodias was there, but really, one could get by without her. The stock of characters also included a Gypsy Man and Woman, a Horse, a Cossack, a Jewish Man and Woman, a Beau and a Lady, and so forth, depending on the thrift and workmanship of the puppeteer who owned the vertep. These puppets were needed for the second half of the show, the profane part.

Seminarians naturally knew all the church songs by heart and performed them beautifully. (Those who couldn’t sing weren’t able to become priests.) To the admiration of the laypeople, they could speak “learnedly” and tell the Christmas story properly. In the villages, this was highly valued. And a puppeteer, lord of the vertep, added the salt and pepper to this ancient sacred story: he changed his voice when speaking for different puppets. And at this intersection of crude burlesque, almost a farce, with a reading of the sacred story, the true folk vertep was born.

Sometimes the box was driven around the village on a sleigh—accompanied by a crowd of children with a star—and a performance was given at every house where the owners allowed it (a special ceremonial discussion with the host became part of the caroling ritual). Sometimes a stationary vertep was set up and then the whole village gathered to watch the puppet show. The sexton would come out and light candles—and the show would begin.

The action in the vertep was quite varied, such that the showman could vary certain episodes to his own taste. But at the beginning, the show took place in the upper level. Candles were lit, wooden angels “went out” to the cave, and Christmas “orations,” or poems, were read. Musicians or singers would accompany the vertep, singing carols describing the Savior’s birth, such as the following:

A new joy has come, unlike any before:

Above the cave a bright star shone its light.

Where Christ was born, of the Virgin made flesh,

As a Man wrapped in swaddling clothes beside God.

But of course, many towns weren’t visited by the puppeteers with the vertep, and the villagers didn’t always have the zeal, strength, or ability to put on a show on their own. The rehearsals needed to start in October so that everything would be ready by the Christmas holidays, and it wasn’t always possible to find a director who had his own copy of the text.

Carols

Happily, there remained the most ancient and simplest way of honoring the holy Christmas holiday: carolers walked around the village dressed as angels and “Persian kings” (with paper crowns on their heads and straw epaulettes on their shoulders), carrying a colorful lantern on a stick—or a star made of paper or plywood with a candle inside it. They paused beneath windows and sang carols in chorus, praising the Infant and Virgin, imploring a Divine blessing for the master of the house and his family.

Both adults and children went caroling, but in different groups—and they tried not to run into each other. It was thought that the more carolers wished a family fortune and success, the better. All the gifts received—food, sweets, coins; and if there were adults in the group, these included alcoholic drinks—were put into a communal sack, and after the caroling was over they were consumed in a friendly manner.

There were various carols. The performance of carols “in praise of Christ” was quite orderly, but there were also “sowing” carols that recalled ancient pagan rituals, which were devoted to subjects of fertility, child-bearing, abundance, and plenty. Mummers played the roles of goats, bears, or “old ladies”—dressing up in a woman’s dress was a surefire comic technique. They conducted themselves freely, putting on masks, covering their faces in soot or flour, making indecent jokes, and carving giant teeth from turnips in parody of a corpse. Those who put on masks were expected to dive into a cross-shaped ice-hole on the Epiphany Day to wash away this sin.

Here’s how a true bard of Rus, Ivan Shmelyov, describes the “singing of praise” and the live vertep:

There is loud stamping in the hallway. Little boys, blessings… All my friends: cobblers, furriers. In the front is Zola, a slender, one-eyed cobbler; he’s very mean, grabs little boys by their tufts of hair. But today he’s kind. He always leads the hymns. Mishka Drap carries a star on his stick, that is, a cardboard house: the paper windows shine crimson and gold from the candle inside. Little boys sniffle, smelling of snow. “The Magi are traveling with the Star!” Zola says happily. “Give the Magi shelter, meet the Sacred, Christmas has come, we begin the ceremony! The Star goes with us and sings a prayer…”

He waves a black finger and they start singing in chorus:

“Your Nativity. Christ Our Lord…”

It looks nothing like a star, but that doesn’t matter. Mishka Drap waves the little house, shows how the Star bows before the Sun of Truth. Vaska, my friend, another cobbler, carries a giant paper rose and keeps looking at it. The tailor’s boy Pleshkin wears a golden crown and has a silver sword made of cardboard.

“This will be our King Kastinkin, who cuts off King Herod’s head!” says Zola. “Now we will have the holy show!” He grabs Drap’s head and places him like a chair. “And the little blacksmith will be our King Herod!”

Zola grabs the soot-smeared blacksmith and places him on the other side. A red leather tongue is hung under the blacksmith’s lip, and a green cap with stars is placed on his head.

“Raise the sword higher!” shouts Zola. “And you, Stepka, bare your teeth in a more frightening way! I still remember this from my grandmother, from long ago!

Pleshkin waves his sword around. The little blacksmith rolls his eyes and bares his teeth frighteningly. And everyone starts up in chorus:

“Herod, o Herod. Why were you born? Why weren’t you baptized? I’m King Kastinkin. I love the Infant. I’ll cut off your head!”

Pleshkin seizes black Herod by the throat and hits him in the neck with his sword. Herod falls like a sack of flour. Drap waves the house over him. Vaska gives King Kastinkin a rose. Zola speaks rapidly:

“King Herod has died a vile death, but we praise Christ and carry him with us. We don’t ask anything of our hosts, but we’ll keep whatever they give us!”

They receive a yellow paper ruble and each gets a haslet pie, while Zola is given a green glass of vodka. He wipes his face with his gray beard and promises to come in the evening to sing “more authentically” about Herod, but for some reason he never comes.

After the Revolution, the tradition of caroling was cut short, and—alas!—it never came back. Now one can hear carols either at a traditional quasi-folk promenade or at a concert of musical devotees who have gathered folk songs and rituals bit by bit and carefully preserve whatever they have miraculously managed to search out.

A great many Internet sites claim to have “real Russian carols,” but on closer inspection the majority of these texts are more or less accurate counterfeits of folk creativity, trite standard greetings from New Year’s postcards.

We can only learn authentic Russian folklore from those who are regarded the true star folklorists—the Sirin ensemble, Sergei Starostin, the folk singer Lukeria Andreevna Kosheleva… And to return once more to the Russian literary classics that have inscribed for us the full beauty of a Russian Christmas.

The snow is dark blue and heavy, it squeaks just a little. There are snow banks and mounds along the street. The pink fires of icon lamps show in the windows. And the air is... dark blue, full of silvery dust, smoky, filled with stars. The gardens steam. The birches are white apparitions. Jackdaws sleep in them. Fire smoke rises high in columns, up to the stars. A starry ringing sings out, floats, and doesn’t stop. A dreamy, miraculous ringing, an apparition of ringing, praises God on high—Christmas.

You walk along and think: now I’ll hear a gentle refrain of prayer: simple, somehow peculiar, childish, warm…and for some reason you see a bed and stars.

Your Nativity,

Christ our God,

Has lit the world with the Light of Reason…

And somehow it seems that this very old sacred refrain…has always been. And will be. (Ivan Shmelyov, “Christmas”).

New publications

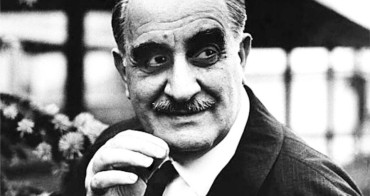

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

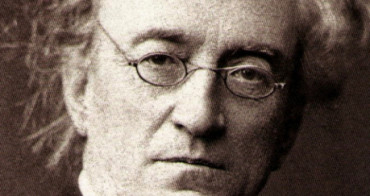

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...