Slavic Brothers or Historical Enemies?

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Slavic Brothers or Historical Enemies?Slavic Brothers or Historical Enemies?

Alexander Goryanin

Poland appears frequently in the Russian informational space, but sadly, it appears almost every time for a painful reason. This results in a corresponding tone for discussions in online forums. Of course, even a passing familiarity with these forums will show that a typical Russian, especially a young one, does not have a high level of knowledge about Poland (to say the least). And this is too bad, since Russo-Polish relations are very instructive.

Every country in the world is different, but many of them are still perceptibly similar to their neighbors. Poland in particular takes pride in not resembling any country in the world—which is partially true. For example, in terms of the population’s level of religiosity, they say Poland outdoes Italy, Spain, and the countries of Latin America, becoming in the 20th century the “most Catholic country in the world.” And this is after over four decades of communist reeducation!

Poland and Russia

Russia celebrated one millennium of existence as a state in 1862. Poland marked the equivalent anniversary in its own history 104 years later, in 1966. Relations between these two countries stretch back at least ten-and-a-half centuries. That’s a long time. Long periods of this history have been darkened by wars and rivalry in the political, religious, linguistic, and economic realms. Still, it would be incorrect to say that there has been “ceaseless warring” or “continual and unvarying enmity.”

During the first three centuries of our shared histories, wars between us rarely exceeded infighting among princes. And these princes would bring their clansmen—princes from Russia, Poland, Germany, Sweden, or Hungary—into the fray.

The Polish political commentator Józef Mackiewicz writes about the Polish Piast ruling dynasty: “It is difficult not to give in to the impression that the Piasts and the princes of Galicia, Kiev, Chernigov, Turov and Novgorod where one big family.”

“The Roman Curia,” Mackiewicz continues, “played a decisive role in changing these ‘familiar’ relations.” For example, in 1308 the “Polish prince” Władysław Łokietek (the great-grandson of Igor Sviatoslavovich, the hero of the poem The Tale of Igor’s Campaign) directed his forces eastward at Rome’s instigation under the slogan of fighting against the “schismatics,” that is, the Orthodox.

Centuries later, a Polish invasion exacerbated the Time of Troubles in Russia. The invasion began in 1605, reached its apogee in 1610-1612 when the Poles occupied the Moscow Kremlin, and ended only in 1618 at the cost of giving them Smolensk, Chernigov, and Briansk. The events of the Time of Troubles are sufficiently well known. We will only mention that this was Russia’s first direct “acquaintance” with Poland. Every witness mentioned the impudence, arrogance, and pride of the invaders. During these events, the Polish nobility managed to firmly adopt a myth that they were the scions of proud “Sarmatians,” the forefathers of the European knighthood and had not familiar connection with the common folk.

Along with an idiosyncratic code of honor, this myth defined the visible traits of the Polish elites for centuries—for better or worse. Their traits certainly included its infamous “arrogance,” as well as patriotism and courage elevated to an ideal. “Sarmatism” didn’t only condition a range of peculiarities about the Polish state (including its messianism), but it also in many respects defined this country’s course. This conservative and aristocratic republic of nobles (with an elected king) was incapable of making concessions, even rational, necessary, and life-saving ones.

Several years ago, searching for the reason why many, if not the majority, of his compatriots felt hostility toward Russia, the Polish commentator Pyotr Kuntsevich wrote: “At one point we were rivals. Several centuries ago we also wanted to form our own Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian Empire. It’s impossible to deny that you won, just as it’s impossible to escape the hatred of the defeated.”

Fall of the Polish Republic

In the 18th century, Poland inclined sharply toward its downfall. Overly insistent Polish proselytism had the opposite of its intended effect. While propagating Catholicism, the zealous Poles provoked internal wars. Peasant uprisings shook and devastated the country on many occasions, as did revolts by the haydamak and Zaporozhian Cossacks, which were largely fueled by an offended religious sense. Equal rights for “dissidents” (Orthodox and Protestant), on par with Catholics, would have removed half of the country’s problems, but the nobility stood still, which accelerated the general degradation of the Republic.

The loss of self-sufficiency happened step-by-step. During the Northern War, the Republic became an unofficial protectorate of Russia, which was a result of the decisions made by the “Mute Sejm” in 1717. During the 18th century, Russian military forces entered Poland quite freely on several occasions. King Stanisław Poniatowski took the throne in 1764, thanks to the Russian ambassador Nikolai Repnin. Repnin pressed for a just solution to the “dissident problem,” but the result was (incomplete) concessions that were nullified soon after.

The idea to divide Poland belonged to the Prussian King. It is worth examining what portions went to each participant. Prussia had long wanted to acquire Polish lands along the Baltic in order to unite their western and eastern parts—and they received these. What’s more, they got Warsaw, Poznan, Bydgoszcz, Torun, and Czestochowa. Austria cut off for itself—besides the originally Polish cities of Krakow and Lublin—Galician Rus, along with Lvov and Ternopol, plus Bukovina. Russia acted more nobly, taking back only the Orthodox and partially Uniate (but certainly not Polish) lands of historic Rus, which were populated by people with a Russian self-consciousness and self-identification. Besides these lands—because of the land’s geography—they took little Lithuania and a piece of what would become Latvia. Also not Polish lands. Catherine the Great said: “We only took what was ours.”

In 1815, the Congress of European powers in Vienna made a final tally of the Napoleonic Wars and gave the Russian Empire a part of the Duchy of Warsaw, which had been created by the French. It’s not clear why Tsar Alexander I decided to take it. Before this, his empire didn’t include a single inch of land that was originally Polish, but now it included the administrative and spiritual capitals of Poland (Warsaw and Czestochowa), as well as Lodz, which would soon become the “Polish Manchester.”

Poles in the Russian Empire

Although it was common at the time for an empire to include parts with foreign languages and nationalities, this partition of Poland was the greatest blow to the Poles’ pride.

The Kingdom of Poland was a massive mistake. It brought the Russian Empire little gain and a large headache. It’s too bad that Emperor Alexander missed the chance to put the final touches on “assembling Rus.” He could have offered Austria the Kingdom of Poland in exchange for Galicia, Bukovina, and Uzhgorod. Of course, the trade would not have been equitable, but it would have made Ukraine’s fate so much happier! Admittedly, it’s easy to make decisions 200 years later when we already know how things will turn out over those two centuries.

The Polish uprisings against Russian control in 1830-31 and 1863-64 were nothing like the popular uprising led by Emelyan Pugachev in the 18th century. These were uprisings by lords who would often have to hang peasants who refused to join them. As such, these uprisings could have seized land not only in the Kingdom of Poland, but also in the adjoining Orthodox districts of the so-called Western region, which had preserved the social structure of the Polish republic. It was based on the Polish landowners; their domination of the lands and economy remained decisive.

Estates in the Western region that were owned by those who participated in the uprisings (or their sons) were subject to confiscation. Thousands of Poles were exiled to Siberia—to this day there is a high percentage of Polish surnames in Siberia. Even those who were indirectly involved in the uprisings and conspiracies were exiled to remote corners of the empire. The Kingdom of Poland was demoted to the Vistula County. As for the Poles themselves, Russian literature created for them a reputation as pompous and absurd people, which has little correlation to their social roles in Russian life.

The Empire gave the Poles opportunities for military and civil careers, as well as for entrepreneurship, that were incomparably greater than they had in old Poland. They actively took advantage of these opportunities, participating in the integration of the Caucasus, Turkestan, Siberia (in this case, they weren’t exiles there), and the Far East, moving en masse to the major cities of the empire (and not only the major ones).

In their new surroundings, they mostly remained Polish patriots—at least in the first generation, though not always in the second. It is worth noting that the percentage of Poles among students enrolled in Russian schools exceeded their proportion of the Russian population. This resulted in the quite visible presence of Polish names among Russian scholars, doctors, engineers, writers, musicians, artists, policy makers, and politicians in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Chief of State

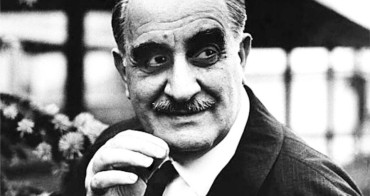

One of the most important results of the First World War was that dozens of new states appeared in Europe. Each of them was born amidst its own particular torments. Poland declared its independence at the moment of the capitulation of Germany and Austro-Hungary in November 1918. It didn’t take long to find a leader. The new leader was the “commander of the armed forces” Józef Piłsudski, who soon became the “chief of state,” a position that sounded strange in the context of the newly reborn Polish Republic.

Józef Piłsudski [Photo: istorik.rf]

Any state has a right to clear and uncontested borders. For Piłsudski and his staff, there was a simple answer to the question of how to draw these borders: according to the maps of 1772. This point of view didn’t coincide with those of his neighbors, and so the Poles resorted to force to reinstate their borders with Germany and the states born from the ruins of Austro-Hungary in five local wars. But these wars were not comparable to the Soviet-Polish War of 1919-1920 on account of the former eastern holdings of the Polish Republic.

Any state has a right to clear and uncontested borders. For Piłsudski and his staff, there was a simple answer to the question of how to draw these borders: according to the maps of 1772.

Poland’s demand to unite all these lands now seems unbelievable. If they were to retain the 1772 borders, Poland would have taken all of Lithuania, Belarus, and the core of Ukraine—after all the border of the Republic before the first partition stretched all the way down to the environs of Kiev. By 1918 there were districts in these regions where the Polish population was no higher than 1-2 percent. But in the Polish government they only argued about whether to give these regions some level of autonomy. Hardly anyone questioned the basis of these geopolitical plans.

Piłsudski—who had been a student at Kharkov University and graduated from a Russian school in Vilnius, and spoke Russian without an accent—confessed to his friends that he had a strange dream as a young man: to seize Moscow and write on the wall of the Kremlin: “Speaking Russian is banned.”

But they ran counter to the plans of Lithuania and Latvia, those of the Ukrainian national republic led by Simon Petliura and the Belarusian Soviet Republic, and those of Denikin’s volunteer army and Lenin’s Council of People’s Commissars and Communist International.

On the Soviet-Polish Front

The Polish-Soviet front formed as early as 1919 in the territories of Lithuania and Belarus. By the end of the summer, Poles occupied almost all of Belarus, and then they concluded a temporary armistice with the Bolsheviks.

"How the Panska Initiative will Finish"/ Soviet-Polish poster from the times of the war [Photo: ru.wikipedia.org]

In September 1919, it looked as if the fate of the Bolsheviks hung by a hair. It was expected that the White Army would take Moscow before the second anniversary of the October coup. At just this moment the Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno struck a blow to the flank of the White Army and an armistice with Piłsudski allowed the Reds to transfer their strike forces to Tula and Orel. Historians will long argue over who did more to save the Soviet government— Piłsudski or Makhno.

The peak of the Polish army’s success came in the spring of 1920, when it advanced on Kiev with the support of two divisions of the Directorate of Ukraine and seized it from the Bolsheviks on 7 May. For many Russians, it was unthinkable that Kiev would be in the hands of the Poles. On 30 May the Pravda newspaper published a call “to all retired officers, wherever they are” to enlist under General Brusilov, who was calling on them to enter the Red Army. According to Soviet historians, around 14 thousand officers responded. By the way, they would hardly have a chance to participate in the “Polish campaign.” On 12 June the Red Army had already retaken Kiev and started moving unstoppably to the west, covering 15 km a day.

Four weeks later, Poland communicated a willingness to limit itself to its ethnographic borders. Nonetheless, the Red Army continued to advance on Lenin’s insistence. With a poor understanding of Poland, he was certain that Polish workers would rise up against the Polish capitalists and landowners when the Red Army invaded, and their German and English comrades would follow their example. It actually provided Poland with an invaluable gift of propaganda. In June 1920 alone, 150,000 volunteers entered the Polish army.

Over just two months, the Soviet-Polish front rolled eastward from 300 to 500 km, leaving behind not only ethnically Polish lands, but also a significant part of Belarus and Ukraine. In 1921, the Russian Socialist Republic was compelled to sign the Riga Peace Treaty, acknowledging the new Polish border.

A New Partition of Poland?

Post-communist Poland often faults the USSR for the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (the German–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 23 August 1939), which resulted in a new partition of Poland. What’s more, they claim that World War II would not have started without this pact.

Let’s think about it. Did the absence of a pact prevent Hitler from invading France? They say that he was insuring himself against a Soviet attack from the east. What attack? There was no shared border between Germany and the USSR before 1939. With or without this pact, France would have still been defeated and occupied. It’s pointless to clam that World War II would not have started without the Pact of 23 August 1939. Having taken care of France and having no border with the USSR (and therefore no fear of a Soviet threat), the Wehrmacht would have quickly occupied every country in Europe that Germany actually did occupy starting in 1939 (with the temporary exception of Poland).

Hitler could have used the forces that he would later so incautiously launch against the USSR to take control of the Mediterranean Sea and Suez, thereby securing oil from the Near East, and next spent as much time as he wanted on England, leaving Poland as a reliable screen from the USSR until later. Instead, by concluding this pact, Hitler created a Germano-Russian border and the precondition for his suicidal war on the east.

What commentators in the West describe as “another partition of Poland” could also be called a “reunification of the Belorussian nation” or a “reunification of the Ukrainian nation,” couldn’t it? Lands that had been largely taken in 1921 and were populated primarily by Ukrainians and Belarusians were now returned to Ukraine and Belarus. Of course, both terms “partition” and “reunification” are open to criticism, but let’s remember the main thing: the new border was on ethnic lines. It mostly followed the line recommended back in 1919 by the Supreme Council of the Entente. Stalin could have repeated the words of Catherine the Great: “We took only what was ours.”

Katyn

The next thorn in the side of Russo-Polish relations is Katyn. I’m referring to the mass execution of Polish citizens, primarily officers, in the Katyn forest near Smolensk in the spring of 1940. As declassified documents show, this was done at the command of the Soviet Politburo.

Katyn Memorial [Photo: ru.wikipedia.org]

When the Germans told the world that they had found a giant grave in the Katyn forest with three thousand victims of the NKVD, the Western allies didn’t look into the question. Amongst themselves, they apparently had no doubt that this mass execution was done by the “Reds,” but the reality of the situation in 1943 convinced them it wasn’t appropriate to criticize the leader of the coalition against Hitler. After the Reich was defeated, the Western countries immediately changed their tune about Katyn. Toward the end of the USSR and afterward, several statements were made at the highest level admitting Soviet guilt and offering the standard condolences. The last of these was the announcement by the Russian State Duma “On the Katyn Tragedy and its Victims,” passed on 26 November 2010, which affirms that the mass execution of Polish citizens was conducted on Stalin’s direct order and constitutes a crime of the Stalin regime.

We, Russia, have condemned all the crimes of this regime, and we did so not on anyone’s order or with anyone’s permission, but of our own free will.

The Fate of the Warsaw Uprising

Poland’s third major accusation against the USSR (which has been readdressed to contemporary Russia by inertia) goes like this: when the Polish underground army rose up against the Germans in occupied Warsaw in August 1944, the Red Army stopped its advance and calmly observed from the other side of the Vistula river as the occupiers put down the uprising, without trying to help. There was no attempt to take the river by force, and the Soviet command tried not to distract the Germans from destroying the Poles. And if this is the case, this means that the Soviet Union is accountable for 200,000 dead, 500,000 sent to concentration camps and hard labor, and the near-total destruction of the Polish capital.

This is the most assailable accusation. While the rebels were counting on winning and taking back their capital on their own, they categorically didn’t want there to be Russian tanks on the left bank of the Vistula. The anti-fascist uprising in Warsaw was politically directed against the USSR. The leaders of the uprising counted on taking Warsaw in 3-4 days and preparing for the triumphant arrival of the émigré government from London, so that it would be in the role of the “receiving party” for the coming Red Army. In case the Soviet leadership didn’t recognize the authority of the émigré government, there was a plan for the “demonstrative armed resistance to the Russians at the capital’s barricades,” in anticipation of help from the Western powers.

The Polish émigrés hoped to use the forces and sacrifices of the Red Army to clear Hitler’s forces from all of Poland, except Warsaw, where they would take power themselves as a rebuff to the plans of the Soviet leadership. It’s certain that they were ready to make sacrifices themselves, and they did make them, but they were unable to be realists.

The horrific losses occurred largely due to this immoderation. And also due to an underestimation of their opponent and other defects.

Consolation Prizes for Poland

As a result of its new borders after the war, Poland, which had previously shattered due to contradictions between various nationalities, became for the first time in its history an ethnically homogenous state, and it remains one. With the permission of the USSR, the Poles banished the Ukrainians in 1945-49 and the Germans, and under the rule of Władysław Gomułka in the 1960s they pressured Jews to leave the country. If Poland hadn’t joined the “socialist camp” and gained the “fraternal protection” of the USSR, it would never have dared to do this. Finally, the Białystok region of Belarus was returned to Poland shortly after the Red Army liberated it from German occupation. At the same moment, adjustments were made to Poland’s advantage in its southeastern corner as well—in particular, it regained the important city of Peremyśl, which had been part of Ukraine since 1939.

When two people speaking about the exact same things (or phenomena, events, objects, or suchlike) come to opposite evaluations while each being certain that they are basing their arguments on facts, this situation is called an antinomy. Of course, I have not enumerated every Russian-Polish antinomy, though I believe I have listed the main ones. They interfere with positive relations between our countries, but this will not always be the case. Not only are our shared interests an assurance of this, but so are the millions of connections between our cultures and people. An enemy is often a misunderstood friend. We can be—and will be—friends.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

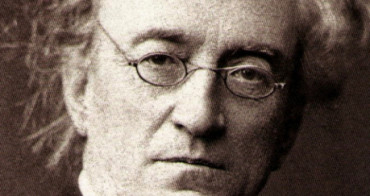

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...