Ludmila Selinsky: Life Abroad is Unthinkable Without Faith

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Ludmila Selinsky: Life Abroad is Unthinkable Without FaithLudmila Selinsky: Life Abroad is Unthinkable Without Faith

Julia Goriacheva

Ludmila Rostislavovna Selinsky (USA) is a member of the Congress of Russian Americans, the Russian Nobility Association in America, and the Council of Directors for the Otrada association for cultural education and aid. She spoke with Russkiy Mir about the fates of several generations of her forebears after leaving Russia, as well as her own work to preserve Russia’s cultural heritage.

– My father, Rostislav Vladimirovich Polchaninov, is working on the third volume of his memoirs, where he elaborates on this subject with examples from the lives of his family and contemporaries. The previous book, We Sarajevan Scouts: Children of the White Resistance, narrates how Wrangel’s army retreated from the Crimea in 1920 with weaponry and thousands of refugees, leaving a great power with the goal of returning. I’ve remembered this key moment in our family history since early childhood. It brings together all that’s most important: deep faith, an ardent love for Russia, and hope for its salvation.

Ludmila Selinsky

My father was born in Novocherkassk in 1919, during the Civil War. His father was Vladmir Pavlovich Polchaninov, a colonel in the camp of the High Commander. At this time, the English decided to evacuate the sick and wounded to Egypt. My father was among them as a newborn. But my grandfather didn’t leave with the rest of the family, staying instead with the commander. When Wrangel called on the “soldiers who were sufficiently recovered to return to the ranks,” my grandfather asked his family to come to the Crimea. “The Russian consul in Egypt,” my father writes, “tried to convince us not to return, since there could be a catastrophe any day. Nonetheless, we returned in October, though we evacuated on 15 November… We were émigrés, not refugees—I heard this expression from my parents and their friends. By the way, they considered only their own ‘Crimean’ evacuation to be émigrés. They called the ‘Novorossiya’ evacuation refugees, except the men, who were just deserters…”

– Could you explain their perspective on this?

– The “Crimean” evacuation couldn’t forgive the “Novorussiya” group for not responding to Wrangel’s call to keep fighting… For the White resistance, service to Russia was the highest duty. Those who made the ultimate sacrifice could not save Russia, but they preserved her honor.

The Kingdom of the SCS (Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which would become Yugoslavia in 1929—Ju.G.) was the only country among Russia’s allies in the First World War that would accept Russian immigrants as their own and offer them aid. After leaving with Wrangel in 1921, colonel Polchaninov’s family arrived there as well.

The family traces back to Polotsk, now in Belarus, and are registered in the Sixth Book of the Nobility. Since my childhood I’ve heard stories and read with great interest about the Polchaninovs who served Ivan the Terrible and fought with the Romanovs during the Time of Troubles.

While he was serving in the Headquarters of the High Commander, my grandfather befriended the commanding officer of the famous Savage Division and knew how loyal these Kazakh soldiers were to Russia. He knew Kalmyks who, just like the mountain dwellers of the Caucasus, fought on the side of the Whites and retreated with Wrangel.

As soon as they could, the émigrés founded Russian schools. They acquainted their children with Eastern Orthodox traditions and Russian culture. They instilled in them the values of honor, loyalty and service to the nation, charity, and aid for one’s neighbor.

I learned the truth about the Russian Empire from my family’s history. It wasn’t a “prison of nations.” People of different nations felt Russian and were loyal to Russia. Concerning “Ukrainianism,” before 1917 no one divided the Russian nation into Belorussians, Little Russians, and Great Russians. Ukrainians didn’t support Petliura but went to fight for the “United and Undivided” Russia. The White officers among whom my father grew up considered themselves Russians, while knowing Ukrainian and singing Ukrainian songs, while my grandfather, who was part of the Asatiani family, sang the Georgian song “Mravalzhamier.”

He lived the greater part of his life in Yugoslavia, where he was buried with military honors. Like his military friends, he was a member of the Russian All-Military Union, which was devoted to the idea of freeing Russia from the Bolsheviks and returning home. But time passed and this hope was passed along to the next generation.

See also: Aleksei Rodzianko. Maintaining a Connection to Russia

As soon as they could, the émigrés founded Russian schools. They acquainted their children with Eastern Orthodox traditions and Russian culture. They instilled in them the values of honor, loyalty and service to the nation, charity, and aid for one’s neighbor. Every boy dreamed of being a cadet and joining the ranks. Many, like my father, served in the church. Christmas parties and Easter entertainment were arranged for the children. There were patriotic extracurricular circles and organizations for children and youths: the “Russian Falcons” and “Recon Scouts.” The Falcons’ motto was: “Strength in our muscles, courage in our hearts, our homeland in our thoughts.” The rules for the Russian scouts began: “The scout is faithful to God and devoted to the Motherland.” They held courses, lectures, and summer camps. A system for training extracurricular instructors was organized under the slogan: “Blaze and kindle!” Even under difficult conditions, cultural life was bustling, though the dream of returning to Russia didn’t fade—even for those who never saw it.

In the book Youth of the Russian Emigration: Memoirs 1941-1951 my father tells the story of the second generation of the emigration. In the prewar years, the Bolsheviks were worried about the White emigration. The men who had fought under General A.P. Kutepov were working at the Russian All-Military Union at this time. The Bolsheviks managed to poison General Wrangel in 1928—this is what his daughter, Natalia Bazilevskaya, told me. In 1930, General A.P. Kutepov was abducted, and seven years later so was General E.K. Miller, who had taken his place as director of the All-Military Union. There are a great number of publications and studies about this period.

Evacuating the Crimea (1920) [Photo: istoriia-evpatorii.rf]

I must add that the Assembly of Russian Officers hosted a congress of the youth from Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, France, and other countries who would join the Russian Youth Union (called the National Union of the New Generation after 1931) in 1930. At the age of twelve, my father met the intelligence scouts with whom the White Officers and members of this group worked. In 1934, he started working in the Russian Falcon group, where all these Russian scouts also signed up. My father continued to do edifying work, later entering the law department of Belgrade University.

Another war started, and people started asking, “what now?” The Russian immigrants divided among various countries all answered this question in their own ways. In France, hundreds joined the Resistance… The Russian scouts moved on to underground work. As their leader, my father made his way to the Pskov Mission, which was made up of “White Russian” missionaries from the Baltic region. The priests in this mission included the princes Nikolai Trubetskoy, Konstantin Shakhovskoy, and Georgii von Bennigsen—my father taught in his school. He risked his life more than once and was twice arrested by the Germans.

As he attests, “life and work during the German occupation amounted to an endless fight against the Germans for the soul of the Russian people, carrying the message of Christ’s love and truth, a message of comfort and hope.” The missionaries managed to help the Russian prisoners-of-war and underground resistance, where my father met his future wife, a woman from a repressed family in Pskov. My mother worked with the partisans and saved prisoners-of-war. They left after marrying, and the remaining missionaries were sent to the Gulag after the war. With the end of the war, the epoch of displaced persons, refugee camps, and the life of the third generation all began.

– Tell us a little about the paths that brought you to New York.

– My recollections of childhood are associated with life in the barracks for displaced persons in Münchehof and Schleißheim. I remember an unpleasant episode when my friend and I were sent to something like a German nursery, and the nuns there knew we were Orthodox but nonetheless tried to force us to be baptized as Catholics. I stubbornly refused, so they slapped me across the knuckles with a ruler. Then, my parents moved me into a Russian kindergarten as soon as they could.

My first role, as the Dead Princes in Pushkin’s fairy tale, revealed to me the world of Russian culture. The refugee camps had people from every emigration, from the “Whites” to those who were just recently “Soviets,” and there was even a Cossack camp. It almost felt like I was living in Russia.

See also: Making the Russian Presence in America More Visible

The Russians made everything with their hands: they built a church from barracks, drew pictures for the schools, managed to make costumes and stage decorations from virtually nothing. I loved the folk games, songs, and circle dances that my mother and other parents led for us. Despite his workload, my father continued his scout work with the youth. We all sat on our luggage waiting to find out which country would take the “displaced” (something that neither I nor the other children understood at the time). In 1951, with the help of the Tolstoy Foundation, my family moved to the United States.

Life wasn’t easy. The cream of the Russian intelligentsia often worked in factories. But everywhere Russians came, they would first build places of worship, which became centers of spiritual, cultural, and social life.

I was horrified by noisy, crowded, and dirty streets of New York, which replaced the forests of Bilibino for me. I was horrified. I expressed my childhood melancholy in drawings that showed either my beloved “hamlets and princesses,” as my mother called them (which I called Russia), or the sad, gray boxes of New York (which I called America)…

Life wasn’t easy. The cream of the Russian intelligentsia often worked in factories. But everywhere Russians came, they would first build places of worship, which became centers of spiritual, cultural, and social life. The first churches of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in the borough of Brooklyn (where we arrived) were built on the ground floors of buildings for rent. “Saturday school” classes were held there as well.

Girls at a church Saturday school, USA

We knew that there also existed an older colony of “old-timers” who had come to America back in the 1920s, consisting mostly of Carpatho-Russians. They built a large cathedral in the Muscovite style in our region in 1935. They belonged to the American Metropolitanate (now the Orthodox Church in America). Many didn’t speak Russian, and part of the service was in English.

The parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia gradually moved into their own buildings. Beginning at the age of eight, I studied at the Saint Joseph school at the Archangel Michael parish, where my father taught history. It included children of the “first (White)” and “second (Soviet)” emigrations, which gradually started to coalesce in to a single Russian émigré culture.

At the time our school was considered the model parish school in New York. At school we learned about the Divine Law, Russian language, Russian and world history, and geography. We were introduced to our great culture and cultivated a love for our Fatherland. We had an anthem to the tune of the Preobrazhensky March with the words “We will love Holy Rus truly, firmly, with all our heart and preserve the precepts of our loyal ancestors solemnly and zealously...” We also had a march that began: “We are the children of great Russia, the hope of our wandering fathers, and our sacred ideals are faith and love for the Fatherland.” They were both written by S.N. Bogoliubov, a teacher at our school.

It was hard being Russian when my classmates in American schools were calling us “reds” or “Communists,” that is, enemies. But in the Russian school we met friends, felt comfort, and gained knowledge that would later be useful in college.

We celebrated Christmas with the Orthodox Church, on 7 January (rather than 25 December other American neighbors). The Christmas parties at the Russian school had Santa Clause, dance circles, songs, and performances. I remember reading the poem “I’ve never seen Russia...” which ended with the words: “and I’ll return to you not as a foreigner but as your native, loving daughter.” We had a uniform like those in Russia, with a cape and crest, as well a journals and a school magazine Snowdrop, which published my article “We Won’t be Ashamed of Our Russian Names.”

It was hard being Russian when my classmates in American schools were calling us “reds” or “Communists,” that is, enemies. But in the Russian school we met friends, felt comfort, and gained knowledge that would later be useful in college. I’m still friends with one of my classmates to this day. Vladimir Kirillovich Golitsyn became the elder of the Synodal Temple of the Russian Orthodox Church in New York, vice president of the Russian Noble Assembly in America, a member of the Cadets’ Union, and an active participant in OYRS (Organization of Young Russian Scouts—Iu.G.).

I finished the Russian school and entered a high school in Manhattan, where they taught art in addition to the academic program. One time in the parish, I was asked to help with a performance of Gogol’s “Night Before Christmas,” and later to teach the children Russian dances. I drew stage decorations and designs for costumes, arranged musical accompaniment, wrote choreography… So began my many years of work on Russian school productions. I was invited to “youth” ball committees, where I helped create an artistic program.

In the summer, many people went to scout camps and to the St. Vladimir’s Day celebration in the neighboring state of New Jersey, where there were outdoor festivities and picnics. Nearby, there was a Cossack village and the famous museum of the Russian emigration Rodina. We went to celebrate saints’ days at the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville and the Kursk Root Hermitage monastery in New York state, where I met my future husband, Fyodor Georgievich Selinsky, who was also from a family of White émigrés from Yugoslavia.

– Your creative interests are strongly associated with Pushkin. You are a writer and organizer of plays and productions based on his fairy tales. Tell us about that.

– It all started with my Pushkin. His 175-year anniversary was approaching and the directors of the OYRS asked me to oversee a Pushkin festival in which our children and young people would participate alongside professional actors. The program emcee was Igor Novosiltsev, a relative of the Goncharovs [descended from the family Pushkin’s wife]. The performance featured the Liudmila Azova and Tamara Bering, famous singers of the New York opera; the troupe of Andrei Kulik, dancer and choreographer of the renowned Joffrey Ballet; a ballerina of Russian heritage from the San Francisco Ballet, and George de la Peña, a soloist in the New York Ballet of Russo-Argentinian heritage. The circle dances were prepared by my friend, the ballerina Tatiana Pavlova, while the famous choirmaster Alexei Petrovich Fekula took upon himself the direction of the choir.

There were scenes from Boris Godunov, Eugene Onegin, The Queen of Spades, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan, in which I sang the Queen Swan. The anniversary went very well. The New Russian Word newspaper wrote: “the Russian colony will long remember the Pushkin festival and be happy that the older generation has such wonderful young people to take over for them.”

After this success, my friend Andrei Kulik (of Ukrainian descent) suggested the founding of a Russian Musical Theater with a Russo-Ukrainian repertoire with the participation of his dancers.

See also: The New Review as a Mirror on Russian Exile

– What were the relationships between Russians and Ukrainians among the youth at that time?

– Back then, and up until recently, there were a lot of Ukrainians in the Russian parishes and church schools of the emigration who saw Russian and Ukrainian culture as one. They labeled as separatists the Galician Uniates from western Ukraine, who received substantial support from the American government. They tried to influence the others with threats, to drive them away from the Russians. (This was already happening in the displaced person camps, where there were separate subdivisions for Banderites, who then moved to the US and Canada.)

Back then, and up until recently, there were a lot of Ukrainians in the Russian parishes and church schools of the emigration who saw Russian and Ukrainian culture as one. They labeled as separatists the Galician Uniates from western Ukraine, who received substantial support from the American government.

Ukrainians, Belarusians, and others were included in the Union of Russian Peoples abroad, which threw Russian balls every year and even “serious” Ukrainian separatists came to them, and our guys went to dances at the Soiuzivka, a kind of resort in the Catskill Mountains (New York state) founded by the Ukrainian National Union in 1952. And despite the views of their “separatist” parents, the young people found common ground.

In my student years I met a Ukrainian named Sergei Diachenko. Like many of my acquaintances, he studied at Columbia University, where there was an “Orthodox Fraternity” that included Greeks, Lebanese, Copts, and Slavs. He had the idea of founding a Russian Club in the Free Russia House. This was a cultural center for the Russian emigration founded in New York by Prince Beloselsky-Belozersky. It had a great hall for lectures, concerts, and balls; headquarters for social organizations, clubs, and publishing houses; and a museum with precious archival materials and relics of the White Army.

Young Russians from various organizations eagerly supported the idea of a common informal club, and Sergei joked that “even the Russians hadn’t thought of this one.” The Russian Club held parties, artistic meetings, and rehearsals for performances at Russian balls. Many couples met and got married thanks to the Russian Club, since it’s not so easy to find Russian Orthodox companions abroad… I invited many of my friends to help prepare the Russian festival, including my future husband. And I soon became the mother of Georgii.

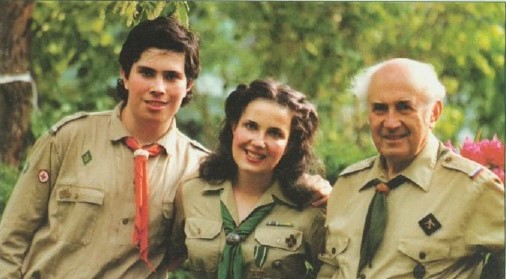

[L.R. Selinsky with her father, Rostislav Vladimirovich Polchaninov and son Georgii]

– And this was the beginning of your family’s fourth generation in emigration?

– That’s right. The preservation of Russian culture continued with Georgii. I sang him the same lullabies that my mother sang to me. And my husband “studied” the beginning of Pushkin’s Ruslan and Liudmila with our son for at six months, and at nine months the boy started to repeat Pushkin’s words after his father. (Of course, Pushkin had played “matchmaker” between the two of us while we were preparing for the Pushkin festival.)

In order to preserve their Russian, parents born abroad most often spoke only in Russian, with their children, even though they often spoke to each other in English. Once they had learned Russian, our children went to an American kindergarten and quickly learned English.

Our son started attending church and going to classes in the Divine Law for preschoolers, just like his father and grandfather did before him. When he was a little older than three, we took him to a scout camp in the picturesque Adirondack Mountains in New York State, where there was a program for children. Beginning at the age of six, he went to kindergarten at the parish school at the St. Seraphim Church in Sea Cliff.

Interestingly, this region is often called a small piece of American Rus. There are also two Orthodox churches here: the Church of the Kazan Icon of the Holy Mother in the jurisdiction of the Autocephalic Local Church and the Church of the Shroud of the Holy Mother of God (Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia), which was built adjoining retirement homes founded by Beloselsky-Belozersky.

The senior priest of St. Seraphim Church – where the children of Wrangel and other prominent White Army émigré families were parishioners – was the famous Father Mitrofan Znosko-Borovsky, later the Boston Bishop. He baptized me in the church at the camp for displaced persons in Münchehof.

My husband and I became parishioners of the St. Seraphim Church, and I started to sing in our parish choir, where our son also served. My parents and husband started teaching at the church school. And they “enlisted” me to organize school performances with the help of my talented husband, who said at the parents’ meeting: “Problems with your Christmas celebration? Ludmila will fix them for you.” I put on “Russian Fairy Tales,” based on the works of Pushkin. My seven-year-old Georgii played the role of Sadko then Mizgir in The Snow Maiden,and Levko in May Night.

Our kids represented Russians proudly, performing at local Cultural Heritage Days and exhibitions. They were filmed in the video “We are proud to be Russian Americans.” Every summer plays were performed at the OYRS camp. For the 800-year anniversary of The Song of Igor’s Campaign, the whole camp participated in a performance of Prince Igor, and for the 150-year anniversary of Pushkin’s death they performed Tsar Saltan with choruses, dances, ballet, and “miracles,” including 30 Russian folk heroes.

– Please tell us about the important role the Orthodox faith plays for you.

Even though at the beginning of the 20th century certain people were not much for church-going when they were in Russia, when they ended up abroad they nonetheless made building churches their first priority.

– As is evident from my story, life abroad is unthinkable for us without faith, without the Orthodox Church. It has allowed us to remain standing and is the center of our spiritual, cultural, and social life. If we didn’t meet at church, we might not have even known that there were Russians living near us. Even though at the beginning of the 20th century certain people were not much for church-going when they were in Russia, when they ended up abroad they nonetheless made building churches their first priority… I’ll mention that our St. Seraphim Church is a monument to the restoration of a unified Russian Orthodox Church. As our senior priest, Archpriest Serafim Gan (the secretary of our Synod), says, the builders of this temple “passed through camps, and for them the construction of the church seemed to be the most important task at that moment: they needed to thank God. And to Preserve Russia outside the borders of Russia.”

St. Seraphim Church in Sea Cliff [Photo: Pravmir.com]

My family and I thank God that we were fortunate to be witnesses to the restoration of a unified church, and I think that the Russian Orthodox Church’s support for the parishes outside Russia and the organization of cooperative projects and endeavors will reinforce their relationship with these parishes, while also providing an opportunity for parishioners of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia to pass along the valuable experience of such structures as the parish councils and sisterhood, which especially enable the great number of Orthodox communities in the Russian world to survive.

Back in the beginning of the 1990s, when I visited Russia along with a group from OYRS, we piously visited the local places of worship and asked the priests to baptize those members of our summer camps who decided to accept the Holy Baptism. The children said that they would baptize their parents when they got home.

– Our compatriots abroad most often try not to lose their connection to their historic homeland. Is there support in the US at the state level for organizations of Russian Americans?

– Maintaining a connection to Russia is a natural desire even in the most difficult conditions. Just as in days long ago, when the Russian nation was split apart, it continued to be united by the Orthodox faith, a common culture, and, of course, love for the land of one’s fathers. As concerns America specifically, the first (White) emigration and the second (post-War—which, incidentally, included both refugees from the Soviet Union and representatives of the “Whites” from Europe, Asia, and even Africa) didn’t receive any state support.

There existed certain private foundations, such as the Tolstoy Foundation, where Alexandra Lvovna managed to get state support in the post-war years for programs to receive refugees in the USA, and the Foundation of Prince Beloselsky-Belozersky, which was able to offer aid to Russian refugees and émigré organizations.

I must talk only about our own efforts. Ever since the currently active law 86-90 on “nations enslaved” “by Russian Communist imperialism” was passed in 1959, there simply haven’t been any other alternatives. Even when more than 38 Russian-American organizations joined forces to celebrate the one-thousand-year anniversary of the Christianization of Rus, this cultural event of worldwide significance was denied support.

In this law, which was prepared by a fierce Russophobe of Ukrainian descent, Professor Lev Dobriansky, Russians aren’t among the “enslaved.” Russians represent only the eternal subjugators of other nations, even those that don’t exist, such as Cossackia and Idel Ural. Soviet dissidents and representatives of “enslaved nations” received state support from the US even after the fall of the USSR. The protests of prominent Russian Americans and organizations like the Congress of Russian Americans remain ineffective to this day.

– And what is your personal opinion about what steps would be possible to foster neighborly relations between Russia and America?

– We need to have an informational presence and develop our social contacts. America is not monolithic. It consists of many ethnic groups. It’s important to support relationships with various groups, starting with those that are historically closer, such as the Serbs, Greeks, Armenians, and Orthodox Churches, as well as with conservative American groups, who share traditional views with a majority of Russians, in order to resist the current of Russophobia. Inimical relations with Russia are harmful to America as well.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...