The All-Russia Museum of Decorative, Applied and Folk Arts opened in its halls an exposition of drawings by Nadya Rusheva; this was not timed to any jubilee, which is already something rare! The denizens of vernisages may ask: how is this related to the museum's main subject matter? And many representatives of the younger generation have never heard of this name at all.

Anna Akhmatova was once asked whether it is difficult to write poems. “When they seem to be dictated by someone, it's very easy. And if you have to invent them yourself, it's very difficult,” she replied. The same principle applies to artists.

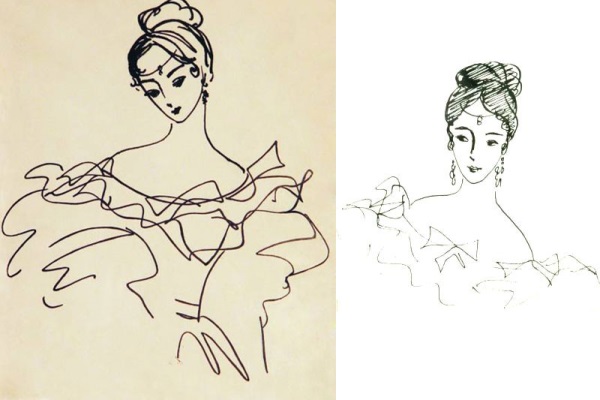

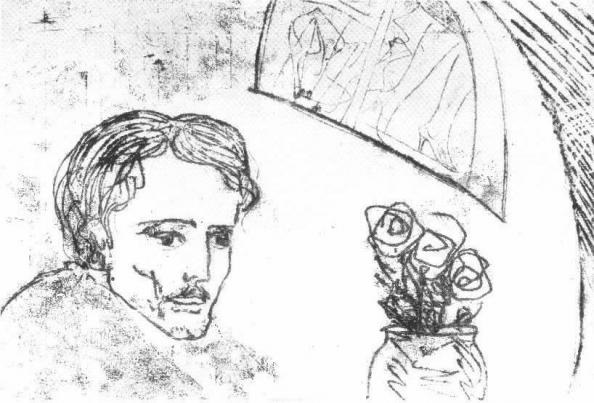

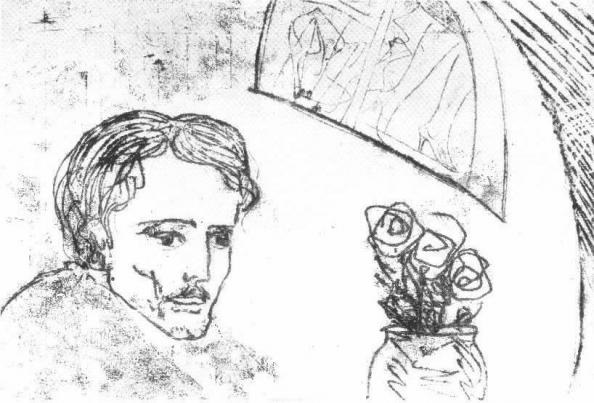

Nadya Rusheva also insisted she did not draw on her own — she simply follows the lines showing through for her on paper like water marks. Everything of genius is simple: as her father was reading fairytales for his little daughter (say, The Tale of Tsar Saltan by Pushkin), she was drawing what she heard using her rich imagination.

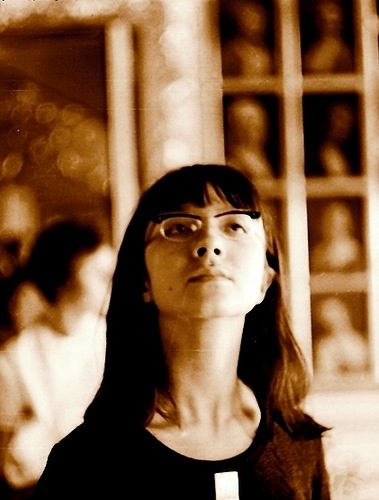

Few can understand how she could create more than 10,000 drawings during 17 years of her life, especially because in her last years she could seldom draw more than half an hour a day. After she became a well-known artist, many adults, recognizing this pupil of an ordinary Moscow school as a child prodigy, have been trying to fathom, grasp and unfold her mystery; yet highbrow scholars were at a loss.

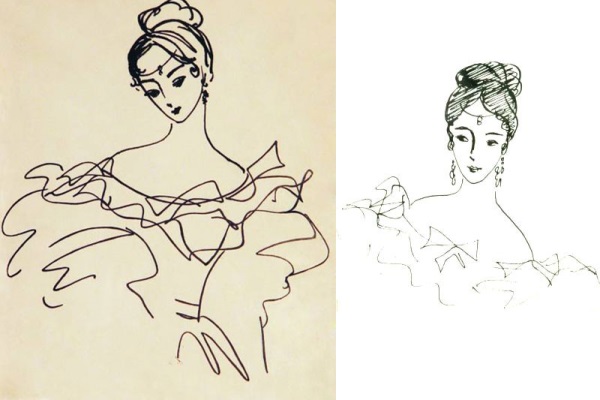

“This girl of genius possessed the amazing gift of penetrating the domain of the human spirit. She worked almost with despair seeking to tell people as much as she could about ballet, antiquity, Shakespeare, Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy, Exupery... How could this 16-year-old girl gain this knowledge of people and epochs? This is a hard nut never to be cracked. People need such art like a breath of fresh air... It's not the matter of technical perfection, but her incredible talent,” wrote Dmitry Likhachev, adding that the maturity of the spirit does not imply an advanced age.

As we all know too well, the public is quick to fall for child prodigies (let's recall the wonder poet Nika Turbina from Yalta, whose life, alas, was also very short). Especially when somewhere in the background some forbidden fruit was lurking, like the novel

Master and Margarita so much disliked by the Soviet authorities, to which a large series of Rusheva's drawings was devoted. At the same time, the public can be incredibly fickle — today long lines of people are waiting to buy a ticket for your exhibitions or performances but tomorrow...

I happened to talk with many people who were better informed than me and they all confirmed that there had been no notable exhibitions of Rusheva in Moscow for about 20 years. During this time a whole generation has grown who are not familiar with her masterpieces.

You won't find any albums of her reproductions in the bookstores — quite different personages are currently in demand. The last absolutely astonishing fact is that while Bulgakov's novel once copied by hand can now be purchased almost at any bookstore, you won't find a single edition with illustrations by Nadya Rusheva, which was the dream of Bulgakova’s wife Elena.

Incidentally, at the exhibition that will last only a month (direct light and drawings are incompatible things) there are no scenes from

Master and Margarita, but there are works from the series devoted to the circus, ballet, Russian fairy-tales, the East and certainly Pushkin. By the way, on one occasion the student Rusheva got unsatisfactory for Pushkin. She stubbornly drew emotions rather than figures without responding to the recommendations of adults that this was the wrong way to illustrate and that she'd better learn from classics. “I draw for my peers, not for Shmarinov,” she once protested. Nadya was lucky in a way, because her talent was not subjected to an official selection at some specialized educational institution. Not in vain did we recall the words of Pele in the days of the World Football Cup: “Do you know why you'll never have players comparable in class with Brazilian players? Because we develop the player's strengths and you correct his shortcomings.”

Natalia Mironova, a former classmate of Rusheva (now a respected researcher), shared with me her recollections that Nadya had distinguished talent not only in fine and graphic art. She also published an independent school newspaper Class-info. In those years such initiatives were not hailed, to put it mildly. “Did not she never get in trouble?” I wondered. “Of course, she did!” Mironova answered. “Some teachers took an awful offense at the way Nadya represented them and the newspaper had to be taken down.” Where are those drawings now, I wonder?

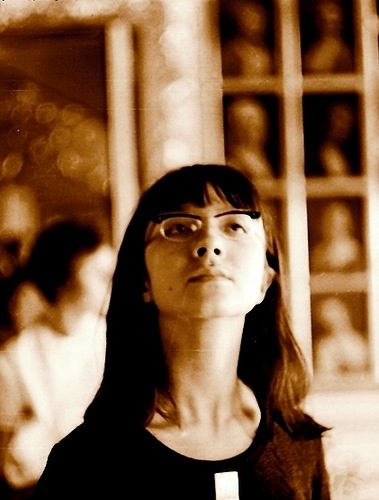

And where does this star fall from? “Blood problems are the most sophisticated enigmas,” Bulgakov's Korovyev used to say. Rusheva was born from the crossing of very dissimilar bloods. Her father was a well-known theatre artist from a family of Tambov peasants. Her mother was the first ballerina of Tyva, Natalia Azhikmaa, who incidentally is still alive. No wonder that nearly half of Rusheva's drawings are stored and exhibited in the National Museum of the Republic of Tyva (but most of her drawings are kept in Pushkin Museum on Prechistenka, though the Moscow audience has forgotten about it in the lack of exhibitions).

Elena Titova, director of All-Russia Museum of Decorative, Applied and Folk Art, told me that even the current exhibition was sheer impromptu event. As part of a large exhibition project devoted to the artistic heritage of the peoples of Russia, currently implemented by the museum, its task force landed in Kyzyl. Workers of the National Museum of Tyva did not conceal their treasures. This is how Nadya's 122 drawings made their way to Moscow.

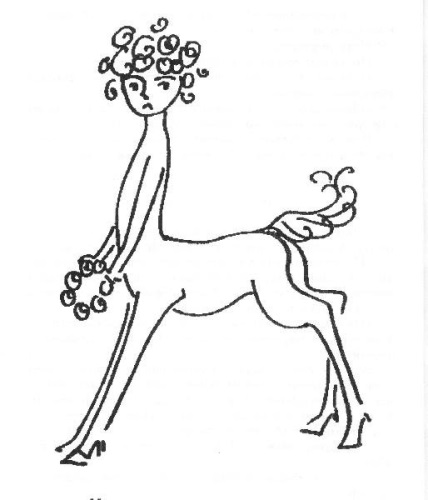

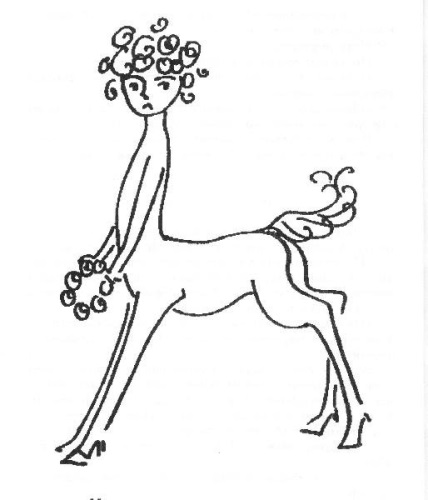

Whether it was mere coincidence or not, the opening of Rusheva's exposition concurred with the unveiling of a monument in her honor created by sculptor Andrei Volkov. The monument seems to connect one of Nadya's most famous drawings Little Centaur with her graphic self-portrait. The monument is set up on Yerevan Street not far from her school that now bears her name. They placed it on the once littered scrap of land now transformed into a charming small public garden. This was an appropriate and timely action, but as Radishchev used to say: “Why the tears, why the tears, my friend?”

Georgy Osipov

Anna Akhmatova was once asked whether it is difficult to write poems. “When they seem to be dictated by someone, it's very easy. And if you have to invent them yourself, it's very difficult,” she replied. The same principle applies to artists.

Anna Akhmatova was once asked whether it is difficult to write poems. “When they seem to be dictated by someone, it's very easy. And if you have to invent them yourself, it's very difficult,” she replied. The same principle applies to artists. As we all know too well, the public is quick to fall for child prodigies (let's recall the wonder poet Nika Turbina from Yalta, whose life, alas, was also very short). Especially when somewhere in the background some forbidden fruit was lurking, like the novel Master and Margarita so much disliked by the Soviet authorities, to which a large series of Rusheva's drawings was devoted. At the same time, the public can be incredibly fickle — today long lines of people are waiting to buy a ticket for your exhibitions or performances but tomorrow...

As we all know too well, the public is quick to fall for child prodigies (let's recall the wonder poet Nika Turbina from Yalta, whose life, alas, was also very short). Especially when somewhere in the background some forbidden fruit was lurking, like the novel Master and Margarita so much disliked by the Soviet authorities, to which a large series of Rusheva's drawings was devoted. At the same time, the public can be incredibly fickle — today long lines of people are waiting to buy a ticket for your exhibitions or performances but tomorrow... Incidentally, at the exhibition that will last only a month (direct light and drawings are incompatible things) there are no scenes from Master and Margarita, but there are works from the series devoted to the circus, ballet, Russian fairy-tales, the East and certainly Pushkin. By the way, on one occasion the student Rusheva got unsatisfactory for Pushkin. She stubbornly drew emotions rather than figures without responding to the recommendations of adults that this was the wrong way to illustrate and that she'd better learn from classics. “I draw for my peers, not for Shmarinov,” she once protested. Nadya was lucky in a way, because her talent was not subjected to an official selection at some specialized educational institution. Not in vain did we recall the words of Pele in the days of the World Football Cup: “Do you know why you'll never have players comparable in class with Brazilian players? Because we develop the player's strengths and you correct his shortcomings.”

Incidentally, at the exhibition that will last only a month (direct light and drawings are incompatible things) there are no scenes from Master and Margarita, but there are works from the series devoted to the circus, ballet, Russian fairy-tales, the East and certainly Pushkin. By the way, on one occasion the student Rusheva got unsatisfactory for Pushkin. She stubbornly drew emotions rather than figures without responding to the recommendations of adults that this was the wrong way to illustrate and that she'd better learn from classics. “I draw for my peers, not for Shmarinov,” she once protested. Nadya was lucky in a way, because her talent was not subjected to an official selection at some specialized educational institution. Not in vain did we recall the words of Pele in the days of the World Football Cup: “Do you know why you'll never have players comparable in class with Brazilian players? Because we develop the player's strengths and you correct his shortcomings.” And where does this star fall from? “Blood problems are the most sophisticated enigmas,” Bulgakov's Korovyev used to say. Rusheva was born from the crossing of very dissimilar bloods. Her father was a well-known theatre artist from a family of Tambov peasants. Her mother was the first ballerina of Tyva, Natalia Azhikmaa, who incidentally is still alive. No wonder that nearly half of Rusheva's drawings are stored and exhibited in the National Museum of the Republic of Tyva (but most of her drawings are kept in Pushkin Museum on Prechistenka, though the Moscow audience has forgotten about it in the lack of exhibitions).

And where does this star fall from? “Blood problems are the most sophisticated enigmas,” Bulgakov's Korovyev used to say. Rusheva was born from the crossing of very dissimilar bloods. Her father was a well-known theatre artist from a family of Tambov peasants. Her mother was the first ballerina of Tyva, Natalia Azhikmaa, who incidentally is still alive. No wonder that nearly half of Rusheva's drawings are stored and exhibited in the National Museum of the Republic of Tyva (but most of her drawings are kept in Pushkin Museum on Prechistenka, though the Moscow audience has forgotten about it in the lack of exhibitions).